Large-scale anti-government protests and collective aggression against leadership and government systems have increased in almost every region of the world since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. With more than 30 significant demonstrations in 26 countries targeting COVID-19 restrictions, the year 2020 was aptly described as “the year of protests”.

A protest is a familiar manifestation of social behaviour that reflects (degrees of) a gap between the government and the governed. Carothers and Press (2020) distinguished four main groups of anti-government COVID-19 related protests: anti-authority lockdown protests, economic hardship lockdown protests, protests against the use of force in COVID-19 responses, and health-worker protests.

The anti-authority lockdown protests, which were the most common, occurred in response to perceived tension between individual freedom ideas vs restrictive public health measures. This type of protest is often, though not solely, driven by misinformation and conspiracy theories and may reflect political polarisation trends and scepticism of science and authority. See for example the thousands who protested in London in September 2020 against the second wave of lockdown restrictions.

Economic hardship lockdown protests made up the second type of protests. They were more common in low and middle income countries (LMICs), and reflected concerns about the impact of lockdown on livelihoods. The third category of protests concerned the use of force in COVID-19 responses, focusing on how restrictions were implemented (in terms of harshness, arbitrariness, and misuse of rules for repressive ends). Finally, health-care workers protested against government responses that left them vulnerable to COVID-19 risks in various countries. In Africa, between March and August 2020 there were 288 COVID-19-related protests by health-care workers calling for better provision of personal protective equipment and better remuneration for extra work done.

While the pandemic is anything but over yet, and various forms of COVID-19 related protests are continuing, there is every reason to believe that mass protests may even increase post-COVID-19 due to economic scarcity and resource competition. Even in settings with low cases or where government responses may have been adequate. Studies on the 2014-16 Ebola epidemic in West Africa and five cholera waves in the 19th century found more rebellions post-epidemic than before and argue that epidemics are incubators of more social disorder (to come). During an active epidemic, epidemic-related protests are very likely to crowd out other concerns. But unresolved pre-epidemic grievances can give rise to stronger post-epidemic protests, especially when there are additional grievances related to the epidemic itself.

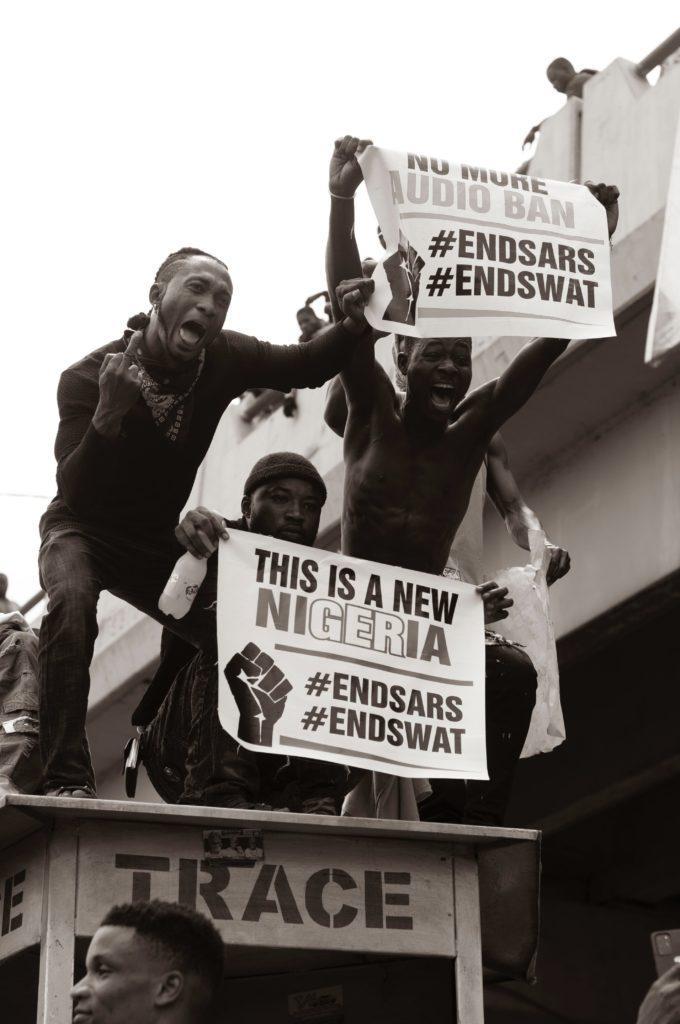

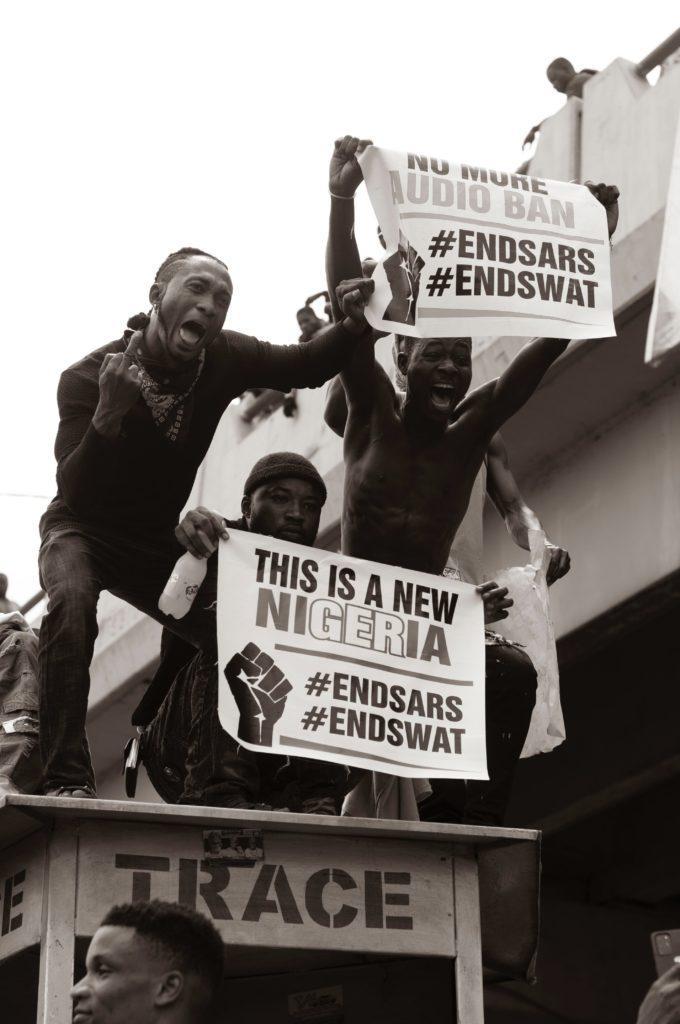

The current global fixation on the COVID-19 vaccine assumes that the vaccine will allow a “return to normal” while underestimating the underlying social grievances that may pose a risk to post-pandemic social stability. We have already seen early signs of how wrong this assumption can be from massive protests like the EndSARS protest in Nigeria and Senegal’s recent protests. This highlights the need to look beyond vaccines and engage in more proactive policy action to forestall the worst impact of coming protests.

In short, we better soon get our act together on post-pandemic protest preparedness (PPPP). That obviously requires tackling some of the root causes, even if macro-economic circumstances are anything but easy now.