Approximately 30% of maternal deaths in Pakistan are attributable to the second delay in the ‘Three Delays Model’ ( i.e. delay in the decision to seek care; delay in arriving at a health facility; delay in receiving adequate care at the facility). Many women who cannot reach primary care facilities have to deliver at home. In complicated cases, lack of access to emergency obstetric and neonatal care can have catastrophic consequences.

In Punjab, the most populous province of Pakistan, the government had scaled up around 1000 basic health units equipped with 24-hour basic obstetric care services by 2017. However, access to these units was challenging for rural communities. The ambulance service provided by the Government of Pakistan, through its routine service delivery model, was hampered by misuse of vehicles, lack of timely maintenance and lethargy in public sector service delivery. Punjab province adapted the national universal health coverage benefits package and essential package of health services to include provision for a rural ambulance service for obstetric and neonatal care. Quality of care in rural ambulance service is being ensured as a part of the package.

The rural ambulance service, launched in May 2017, is designed to collect all normal and high-risk pregnant women from their homes at the time of delivery, and throughout pregnancy for identified antenatal complications. The service can be reached by calling a toll-free number (1034). The ambulance takes the woman to a primary care facility and waits for an initial screening. If the primary care staff need to refer the woman to a higher-level hospital, the same ambulance transports her there. If staff are comfortable conducting a normal vaginal delivery at primary care level, the ambulance goes back to its resting point and awaits the next client.

The government out-sourced operation of the ambulance service through a unique tripartite arrangement: the central call centre is run and managed by a telecoms operator, the day-to-day vehicle operations are run by a private car rental company, and the technical and financial aspects are managed by the government’s Integrated Reproductive, Maternal and Child Health & Nutrition (IRMNCHN) programme.

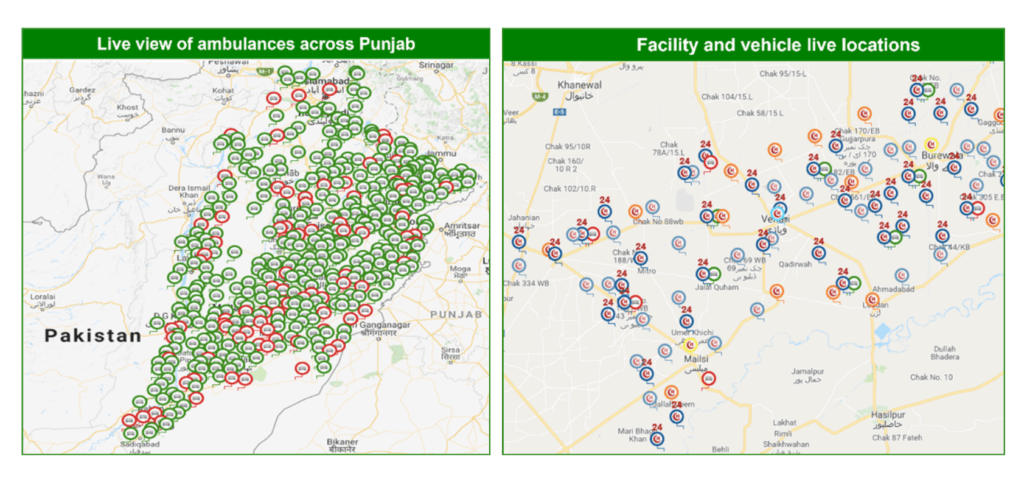

The call centre is manned by a team of call agents who handle an average of 5000 incoming calls per day. A real-time dashboard reflects the ambulance locations through GPS trackers, health facility locations, and other relevant details using Google maps. The call agent’s screen shows the ambulances available in a particular area, and the agent can assign the one nearest to a woman’s home. Once the ambulance is assigned, the agent identifies the nearest health facility from the same map. A text message is then sent to the driver as well as the client as a confirmation. The text message sent to the client contains the name and contact number of the assigned driver and the vehicle’s registration number. The text message sent to the driver contains the name and contact information of the client.

Locating addresses in rural areas is challenging as streets and house numbers are often unmapped, and so most clients and their caretakers are unable to provide exact addresses. The exchange of mobile phone numbers of ambulance drivers and clients/caretakers through automated text messages sent to both parties once a case is assigned, enables them to call and find out the exact location.

Source: Rural Ambulance Service Dashboard

Vehicle operations are overseen by provincial and district level managers hired by the private rental company. The company is also responsible for providing fuel, drivers, and repair/maintenance of the ambulance. The agreement with the rental company enables the government to track the performance of each vehicle continuously through the dashboard. The key condition of the contract was that “the ambulance engine would turn on within two minutes of a case being assigned to the vehicle, and no excuse for driver or fuel unavailability would be acceptable.”

Since its launch, the ambulance service has transferred over three million women from their homes to health facilities, around three and a half million women from primary to secondary/tertiary hospitals, and around 10000 children, aged under five years, for urgent referrals. On average, 2800 women are transferred each day across the province, including public holidays. It has been estimated that at least half of the 500 000 emergency referrals to secondary and tertiary care hospitals have prevented severe morbidity and maternal mortality. The cost per transfer for an average case is approximately US$ 10–15.

The success of the rural ambulance service in Punjab, implemented through an outsourced model, is evident from the reduction in maternal mortality in Punjab (from 178/100,000 in 2015 to 157/100,000 in 2019), increase in skilled birth attendance (from 65% in 2014 to 76% in 2018), and improvement in timely access to maternal care services in rural areas.

Based on this experience, the Government has further expanded the fleet of ambulances to 600, and increased the scope of public-private partnerships to other services.

This is a fantastic initiative very timely and needed to save Maternal and Child health 3 cheers to Ali Jan Secretary Health this was long over due My best wishes to Punjab Government and hope other provinces will follow up Dr Nizam former Director Asia Pacific region UNFPA New York