It was great to be back in Berlin, which I’ve always called “my intellectual city” since the first time I visited it in 2007. Its many streets and parks are named after some of Germany’s – and the world’s – greatest thinkers such as Karl Marx, Max Planck, Robert Koch, and of course, Rudolf Virchow, the Father of Social Medicine and my personal physician hero. This past week, I attended the World Health Summit, one of global health’s annual reunions (another major one is Thailand’s Prince Mahidol Award Conference or PMAC whose ‘political economy’ I analyzed a few months ago). The last time I attended WHS was in 2012 and 2013, after which I was on a hiatus since I made a commitment (as part of lifestyle decarbonization) to skip global health conferences when I’m not needed and if the venue is far from my present location. Now that I’m currently a visiting scholar in ITM Antwerp (thanks to EV4GH), I could easily take an eight-hour-long low-carbon and guilt-free train ride from the city of diamonds to the capital of techno.

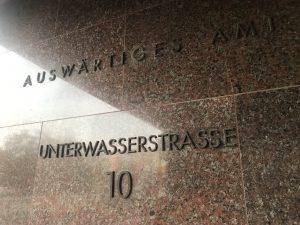

Thanks to the invitation of my new planetary health ‘best friend’ Sabine Gabrysch – Germany’s first professor of climate change and health, my first stop in my week-long sojourn in Berlin was a pre-WHS conference entitled “One Planet, One Health, One Future” (did that sound like ITM’s colloquium ?) which was held at the German Federal Foreign Office and co-hosted by the Wildlife Conservation Society. Eckart von Hirschhausen, a German physician and comedian – indeed embodying the adage “laughter is the best medicine” – even noted in his remarks that the venue was aptly located in Unterwasserstraße, which literally means “under the water street” in German. It seems that Germany is already preparing for sea level rise, while the reality is that the world’s most vulnerable countries do not even possess the resources to put stilts in their houses.

Renzo with Sabine Gabrysch, Germany’s first professor of climate change and health and his new planetary health ‘best friend’

Both the words ‘planet’ and ‘one’ were in the convening’s title, which made one think that maybe this was the chance to resolve the sibling rivalry (or are they really siblings?) between the ‘fields’ of ‘planetary health’ and ‘One health.’ The conference speakers were coming from these different traditions (including another one, Ecohealth), but the outcome document still ended up being called “Berlin Principles for One Health.” The debates about terminologies ensued during the main summit, where sessions organized by The Lancet One Health Commission explored these relationships. Honestly, while I am closely associated with planetary health (I’m even building my own organization called PH Lab with me as its ‘Chief Planetary Doctor’), I am at large agnostic to these terms. I think that these academic debates are a time-consuming distraction from the ultimate mission of advancing the health of both people and the planet – regardless of the term. While it is “nice to know” their historical evolution (i.e., One Health from veterinarians, Geohealth from geologists, etc.), we must ensure that the rich traditions and convergences of these paradigms unite rather than divide us.

Despite the term confusion, I was impressed by most sessions in the pre-conference, especially by the questions coming from the audience. Some speakers introduced planetary health’s concepts and principles and highlighted the nature and urgency of its challenges, while others showcased specific projects and agendas ranging from viromes (viral genome) and the Lancet Climate Countdown to biodiversity conservation and pandemic preparedness. But you could also feel a bit of angst (which is an existentialist concept expounded by several philosophers including the German Martin Heidegger) in the room, reflected in the questions about the need for embracing degrowth as a new economic paradigm and tackling head-on political and corporate forces from Trump to the coal industry. This angst is an indication that the ongoing planetary health conversation must rapidly shift from being a predominantly technical discourse about disciplinary boundaries and research methods towards a more fundamental examination of the economic engine and political machinery that drive planetary health destruction.

The German Federal Foreign Office at Unterwasserstraße 10 – is Germany already preparing for the new normal?

I left the conference thinking that this pre-WHS event should have been the main event. I was under the impression that climate change and planetary health had again been sidelined in an important global health gathering. Two days later, to my surprise, however, the opening ceremony began with these remarks from WHS President Detlev Ganten: “Planetary health defines climate and environment as important determinants of human health. Both imply that we need a holistic view on health which includes our biology, our environment, and our lifestyle and behavior.” He even asked the young people – which he defined as everyone below 40 – to stand up; they comprised more than half of Virchow’s hall. In my mind, planetary health is now front and center in the WHS at last, and the future is bright because of this new generation of planetary healers standing tall – and Virchow himself must be applauding at this glorious sight (I always say that if Virchow were alive today, he would be in the frontlines of fighting the climate crisis, along with Greta.)

My favorite speech at the WHS – and I’m pretty sure it was everyone else’s as well – was the magnificent tribute to Alexander von Humboldt, the “most celebrated naturalist in the world,” delivered by his biographer Andrea Wulf (I still have to buy her widely-acclaimed biography, “The Invention of Nature” – is there anyone who wants to give it to me as an early Christmas gift?). This year, Germany and the world are celebrating von Humboldt’s 250th birthday. Embarrassingly, her speech was my first time to learn about von Humboldt’s legacy to the world – he was the first to describe nature as a web of life and the Earth as a living organism; as early as the 1800s he predicted the occurrence of climate change resulting from the “production of huge masses of steam and gas in the centers of industry,” among others; he was first to elucidate the services of forest ecosystems; and he pushed for the democratization of the sciences by pioneering the first international academic conferences. Together with Virchow, I now have two German role models – Virchow, the Father of Social Medicine, and von Humboldt, the Father of the Anthropocene and the first planetary health doctor.

The following day, the global health elite of the WHS were back on their feet – and back to business as usual. While there were two sessions on climate change and health (which frankly I skipped as it felt like too much preaching to the converted) and another two by the One Health Commission, the rest of the program failed (to a greater extent) to connect (or at least tangentially) diverse global health agendas such as universal health coverage, noncommunicable diseases, migrant health, mental health, pandemic preparedness, antimicrobial resistance, big data, digital health, etc. to the broader existential planetary crisis we are facing (not to mention that the mouthwatering bratwurst on Day 3 disrupted the conference’s hugely vegetarian offerings – thankfully I did an advanced exercise during the previous night’s gala dance). It is a reflection that after all, planetary health is still the “icing on the cake” rather than the chiffon itself; conference architects are still stuck in ‘downstream’ issues like healthcare and diseases; and session panelists are mostly silo professionals housed in orthodox global health organizations and not systems thinkers devoted to overall planetary healing.

Because of the huge chasm between opening salvo and the main attraction, I am not yet sure if this year we have seen the birth of a true planetary health summit. There seems to be no real sense of urgency within the global health community about the catastrophic health impacts of climate change and other forms of environmental degradation – and this is in spite of Richard Horton, wearing a sleek leather jacket, already urging health professionals to protest against climate emergency. There is no guarantee that next year’s WHS and those that are yet to follow will continue to give the spotlight to these civilizational threats. However, I think Germany can be not just a global health leader, but a true planetary health steward if it wants to, and it can start with a yearly planetary health-oriented WHS (and Berlin can proclaim itself as the world’s first planetary health city). Beyond the WHS, other annual global health reunions like PMAC and the World Health Assembly are yet to select planetary health as a theme. Discussing the world’s health through a planetary health lens should not be a difficult task if we view planetary health not merely as a collection of environmental health problems or a new discipline for the new normal – we must treat it as a new frame for debating and envisioning health in the era of the Anthropocene.

In his speech, Dr. Tedros called Ilona Kickbusch the “Queen of Global Health” – and he asked if she had already chosen the king. But who will ascend to the planetary health throne?

The planetary health-ness of the WHS – which was spectacular and even heart-rending at the beginning (Andrea Wulf describes this as von Humboldt’s “emotional advocacy for our planet”) – slowly and surely diminished and disappeared as the days went by. True to the spirit of climate change, the summit had an ‘anticlimactic’ ending with a (dry and emotionless) technical discussion of Geneva neighbors (GAVI and Global Fund) and friends (like the Wellcome Trust) on how to implement a plan – the Global Action Plan for Healthy Lives and Well-being for All. In my mind, they could have just gathered in WHO’s coffee shop for a friendly chit-chat on this (Of course I’m joking – a serious discussion on GAP in front of the global health elite is a must!).

I will end by remembering Dr. Tedros’s quote – he always gives his speeches with a simple yet magnetic flair, a mark of a true politician. “Health is a political choice,” he repeatedly underscored. I will add that where we focus our collective gaze on – whether the signs and symptoms or the “causes of the causes” – that is also a political choice. I hope that in the new political choice that we will make for this generation and for those to come, it will include not just the health of people, but that of the planet too.