(with support from Yaimie Lopez, Kim Ozano & Werner Soors)

On July 28th, António Guterres launched the UN policy brief COVID-19 in an urban world. The brief starts off with the finding that 90% of all reported COVID-19 cases so far occurred in cities, and highlights the critical role local governments play in crisis response, recovery and rebuilding. This is particularly important for Latin America, which – together with its northern sibling – is the most urbanized region in the world: more than 80 % of its citizens live in urban areas. The subcontinent is also the most unequal region in the world. Together with rising poverty rates, and weak health and social protection systems, this explains why Latin America today is the epicenter of the pandemic, according to the joint UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) and Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) COVID-19 report, published on 30th July.

Against the backdrop of these recent publications and trends, I had a thorough look again at a blog I wrote for the ARISE consortium earlier this year, ‘Recommendations from Guatemala to urban municipalities responding to COVID-19 in low- and middle-income countries’. Based on my experience in municipal health policy and with WHO’s Urban HEART policymaking tool, my blog wanted to stimulate critical thought and effective action by local governments addressing COVID-19. We are three months later, and my country is still in what ECLAC and PAHO call the “control phase”. In fact, with now over 50,000 cases for a 15 million population and no sign of flattening the curve, we haven’t controlled anything yet. The economic recovery phase has not taken off, and the rebuilding phase remains a distant dream.

This is not an ideal position for providing recommendations. The critical role of local, urban governments in controlling the COVID-19 pandemic is endorsed today at global level. Accountability mechanisms that have worked well in Guatemala are face-to-face meetings within citizen participation structures, such as the Municipal Development Committees. But most of them weren’t used during lockdown, potentially losing the voices of the most vulnerable and most affected. Yet the case for a stronger and truly inclusive local role in COVID-19 control is stronger than ever. In this editorial, I revisit my blog and offer some humble reflections from my urban perspective.

Collect and use data to identify vulnerable populations

It is unacceptable – both ethically and operationally – if vulnerable populations at local level remain unidentified. Valuable data on vulnerability only become available through coordination within and across municipal operating units and other public institutions. In addition, municipalities should seek partnerships with researchers and social workers who can support data collection and analysis. This can be time-consuming and is often neglected, particularly during a crisis, but is a key condition for effective action. Where these data are available, it is useful to have them visualized in a digital dashboard or through a similar format to facilitate communication and decision making across all actors at urban level. If this is not possible, the data should at least be presented through maps or tables. A stratified view, by neighbourhood or even household, will form the basis of an evidence-based municipal crisis response.

Engage with all community actors

From situation analysis up to crisis management, genuine community participation is key to ensure success in the short, medium and long term. Accountability structures that facilitate the participation of all citizens and promote different levels of involvement, even while staying at home, are relevant. As stated by the UN, to “ensure the most marginalized communities and individuals play leadership roles in immediate response, design and planning efforts”. In addition, recognized civil society groups should be considered as communication channels for reliable information, thereby reducing the paranoia generated often through social media.

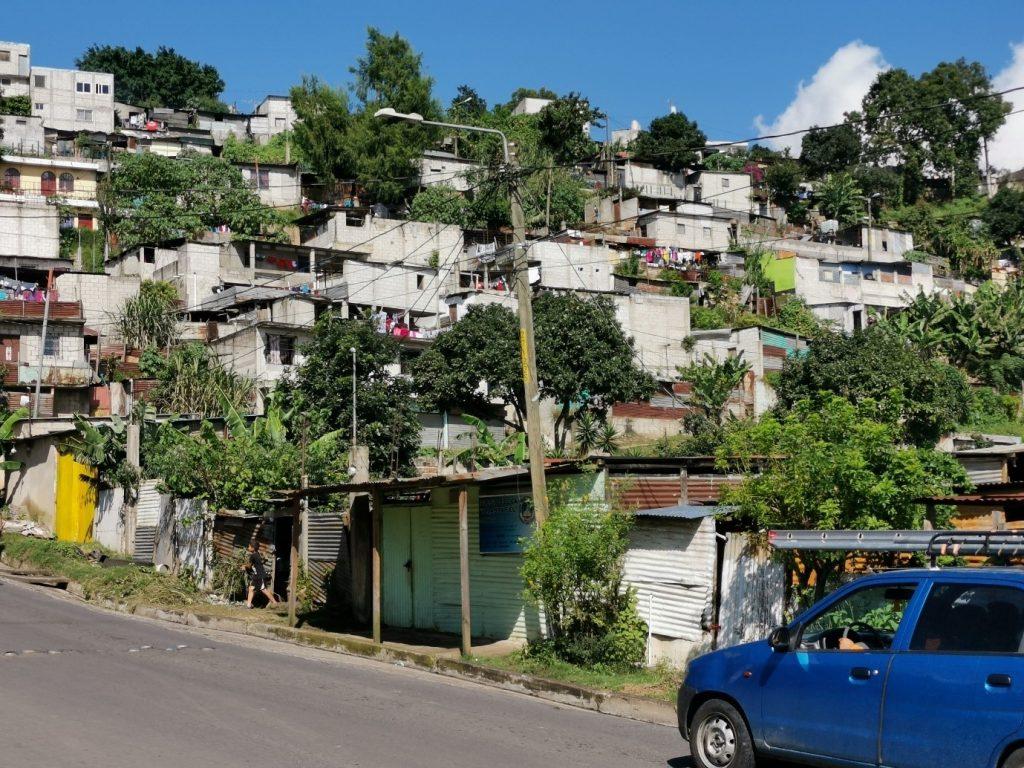

Consider the needs of people living and working informally

Understanding and acting upon the needs of people in urban settlements and/or working in the informal sector is a key challenge. Without access to water, food and basic services, and with pre-existing high levels of violence, people cannot be expected to stay home. Without improvement in these conditions, if home confinement is achieved through force (like Guatemala’s state of siege), the risk of infection in overcrowded homes is considerable. In addition, without access to informal earning opportunities, the already vulnerable in these settlements are at risk of starvation. In parallel, intra-family violence and crime increase. It is at municipal level, and through multi-sectoral coordination and planning, that unfulfilled needs can best be identified and acted upon, creating healthy living and working environments.

Improve and support the local capacity to respond to COVID-19

A good situation and needs analysis without a decent operational capacity makes no sense. In Villa Nueva, the municipality in Guatemala where I work and live, existing Health Policy guidelines can serve as an example of capacity-strengthening action points for COVID-19 control:

In addition, although a local health system is thus very important in the response to COVID-19, local action should also be supported by central government and “public health measures intended to flatten the epidemiological curve should go hand in hand with social protection measures”. Here, one giant step forward would be national implementation of an innovative proposal made a month ago by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean: a six-month basic income for all citizens under the poverty line. At an estimated cost of 2% of GDP, this would avoid a much bigger economic and social loss. The proposal was endorsed by the Pan American Health Organization only days ago. A glimpse of hope and another lesson from Latin America for the world, but one still to materialize…