Here’s a short tale, well known in my country.

Growing up, a child would request to accompany an elder to the nearest shops. The elder would say yes. Time to depart, the child would gleefully trail the elder to the door. At the door, the elder would tell the child to go back in the house and take his shoes. Upon return, with the shoes in its hands, the elder has vanished.

The elder was not being dishonest. Dismissing a request is tough because it has to be done in the face of the child. The promise can be broken at a distance with less burden of shame.

Now, what has this to do with declarative commitments for health? The answer is: a lot. I will anchor my thoughts within the African context, but I believe it can also apply to ‘global health’.

Can we go to the shops together?

The buzzword in global health is solidarity – going to the shops together. In September 2023, three United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) High-level Meetings (HLMs) on health will take place in New York, respectively on pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response (PPR); universal health coverage (UHC); and tuberculosis. In this article, we will focus on the UHC High Level (HL) meeting.

In September, ‘the elders’ (here: heads of state and government) will discuss how every ‘child’ (every citizen in the world, and especially citizens from low-and middle income countries) can get the health care they need without having to sell their cattle or incurring a debilitating medical debt. A lot of energy has already been invested in ‘engaging stakeholders’ to shape the agenda for the UNHLM. Indeed, it’s exciting to plan to go to the shops together. There is already a zero draft of the political declaration emanating from the various consultations. And UHC 2030, a global movement that advocates for building stronger health systems for UHC, has made a strong call to ‘move together towards UHC’, with an 8-point action agenda. So in many ways, thing are looking not too bad, a few months before the UN high-level meeting.

Go back and take your shoes

Nevertheless, it’s good to keep the above story in mind. Indeed, the breaking point for quite some declarative commitments is always when being told “to go back and take the shoes”. History provides us with some examples.

The Alma Ata declaration on Primary Health Care (PHC) was a grand commitment with a lofty aspiration of achieving ‘Health for all by 2000 ’. However, PHC is now a shadow of itself. It’s for a reason that WHO and others emphasize over and over again the “importance of PHC on the road to UHC”. Far too many countries have neglected PHC in recent decades.

Another example. In 2001, African “elders” met in Abuja and committed to allocate 15% of their annual budget towards health. Regrettably, something happened when citizens were told “to go and take their shoes”.

The UN High-Level meeting on UHC in 2019

In 2019 there was a UNHLM on UHC which re-affirmed a commitment to health for all. The declaration, titled “Universal health coverage: moving together to build a healthier world”, resulted in the doubling of country commitments to UHC between 2019 and 2021. However, in 2022, that positive trend stagnated and even reversed in some countries. This can be partly attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic, but it is important to note that despite widespread UHC commitments in the aftermath of the 2019 declaration, at the point of “going to the shops together”, only 11% of countries adopted a roadmap or strategy to achieve UHC. In other words, yes, many commitments on UHC were made after the HL meeting, but in most countries, no concrete steps were made towards financing and implementation. This underscores that if commitments are not carefully managed, they can be an obstacle to the progress they seek to achieve since they can give false comfort that something is being done.

How can declarative commitments be made to work?

The UN HLM on UHC in September 2023, the first one “post-pandemic”, is a grand opportunity. I propose two areas of rethink, directed to civil society and political figures:

1. Civil society should recognize that having issues of concern on the agenda is a notable milestone but not a breakthrough. For the latter, implementation is key. Of importance is to also recognize that to make progress on implementation, civil society doesn’t always need to be confrontational. Yes, petitions can be powerful tools, in some settings, but they can also irritate those in authority, and trigger a vicious backlash. Sadly, as you know, in many settings around the world, there’s a closed and/or shrinking space for civil society involvement. Civil society thus has to tailor its strategies, according to the domestic setting. This includes strategically locating power, and how to engage with it productively to bring about change. Learning the lessons from COVID-19, civil society should also reflect on the limitations of single-issue (disease focused) advocacy and start advocating for health-system wide improvements that are consistent with the tenets of UHC.

2. Political figures should realize that local action is superior to imported optimism. I do not expect less of Africans, but I am driven by pragmatism. Political leaders should keep an eye on the ambition but guided by reality. This is because by design, the discourse on UHC has tacitly assumed that requisite infrastructure and basic tools are in place to steer health systems towards UHC, with emphasis on re-designing health financing systems towards pooled pre-payment mechanisms. However, many African countries lack the basics: running water at the clinic, proper lighting for the local nurse to ‘see’ the patient properly at night or a life-saving antibiotic that costs two US dollars. I am of the opinion that UHC will remain a pipe dream if the foundational elements of the health system remain neglected. Therefore, African leaders should strategically prioritize and sequence relevant reform reforms, starting by directing funding towards the basics, and then build progressively towards the UHC aspiration.

It’s time to go to the shops together

UHC does not happen at the global level in meeting auditoriums. Although the global level is important, UHC mainly happens in homesteads, and it matters more to people who do not even know that the term exists. After the UNHLM, the terms of progress must urgently shift from expressing commitment to ‘doing UHC’. One needs to realize that UHC is not a policy, it is an aspiration, and aspirations are achieved through a process, not wishes. Wishing is most certainly not a strategy. As the Arabic saying goes: ‘A promise is a cloud; fulfillment is rain’. Indeed some declarative commitments on health have remained just clouds, but history does not repeat itself, people do, and history can be undone! The 2023 UNHLM on UHC takes place at a ‘now more than ever’ moment, shaped by the COVID-19 pandemic. But it will be to no avail if there is no follow-through action.

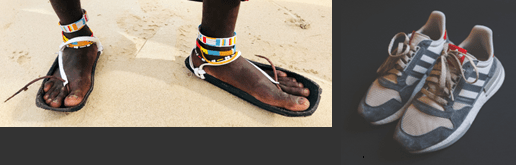

It is time go to the shops together, both domestically and globally – we have our shoes on!