The importance of historical and longitudinal perspectives is finally gaining attention in health policy and systems research (HPSR). HPSR is a field that is concerned with understanding and strengthening complex adaptive systems over time. Rather than magic bullets, our focus is on patterns of behaviour and long-term sustainable change.

In HPSR, and among decision-makers, history becomes important because it is useful to understand change, and whether long-term system-wide interventions had the positive effect intended (e.g. the Good Health at Low Cost series). History shapes the particular context of each health system and ensures that previous successes and failures are properly remembered.

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” – George Santayana

However, despite being fundamentally concerned with change over time, historical methods from the social sciences and humanities have been neglected in HPSR. Specialist tools such as oral history approaches are rarely applied; full historical studies tracing change over time are rarely funded; and health system histories remain an individual interest project.

There is also a significant North-South, or high-income (HIC) low-middle-income (LMIC) divide. For example, while there are multiple publications tracing the history of HIC systems (e.g. the UK’s NHS), there are only a handful of studies tracing the evolution and adaptation of LMIC health systems. Yet HPSR is a field focused on LMIC health systems – and it is easy to see how the features of LMIC health systems are rooted in history. For example, the public-private mix; whether they are centralized/decentralized; whether they are hospital-centric; whether they have a maternal-health orientation. Never mind more nuanced features such as causal loops, tacit assumptions and organisational cultures.

There are renewed efforts to draw like-minded researchers together for further discussion about health system histories (e.g. within the Health Systems Global SHAPES thematic working group). However, the situation is dire, and requires more urgent action. If you accept that the histories of LMIC health systems are important, then you should be feeling alarm at the rapid and permanent loss of historical evidence in these settings.

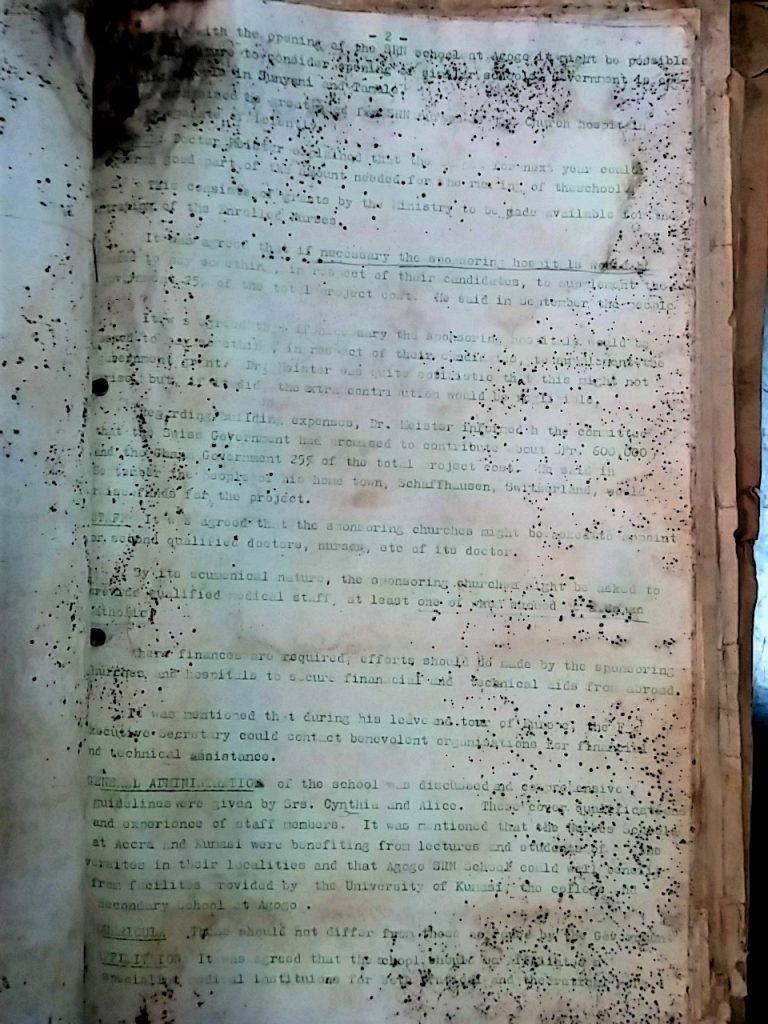

Fieldwork conducted over several LMIC countries has highlighted the rapid loss of archival material relevant to health systems. In some cases, materials have been ‘extracted’ from LMIC settings, and can sometimes be found in HIC archives. For example, where a PHD student has removed materials from the LMIC study site to the HIC academic archive. Or another common example are institutional archives such as those of missionary groups, whose primary materials tracing health system development in colonial times now rest in mother-body European archives.

Of course, there are very few actual archives in LMICs that collect this type of material (physical or digital), and those that exist tend to be neglected. The situation in fragile and conflict affected states is worse. However, even in more stable and middle-income states, health system historical materials such as policy drafts, contracts, maps, reports, Ministry materials, letters, or (pre-internet generated) studies, are rarely placed in organised storage.

During fieldwork on a related study in Ghana, we were told that there are multiple reasons for this. The main reason was that no one considered such materials to be important (compared to say retaining patient records as required). But other reasons were that there were no resources available to build and sustain archives; the primary materials had been ‘taken overseas’; and most interestingly perhaps, that in Ghana, there was a management culture that prevented the storage of health system relevant materials – so outgoing managers ‘swept the decks’ before handing a blank desk to a new incumbent (often with a new political affiliation), and also that in the 1960s-1980s there was a deliberate culture of ‘not leaving a paper trail’ for accountability reasons. It is also important to note that key LMIC health system decision-makers who were active in critical times from the 1950s-1980s, are now in their eighties or nineties. Several key figures who were instrumental in their LMIC health system’s development were tragically lost over the last few years – and before their narrative could be recorded.

History is essential to understanding and strengthening health systems. We are losing key evidence before we even know what questions to ask of it. We need to develop cadres of engaged health system historians in LMIC settings, and local LMIC-kept archives (perhaps to the scale of the Timbuktu Manuscript Projects), that in our digital era can be shared to the benefit of anyone seeking to understand health system’s development.

Welcome to the SHAPES article series, hosted by IHP. SHAPES is a thematic working group within Health Systems Global, which facilitates discussion, debate and collaboration around social science approaches for research and engagement in health policy & systems. In the months leading up to the 6th Global Symposium on Health Systems Research in Dubai (Nov 2020) SHAPES members will be blogging about the Symposium's theme of "re-imagining health systems for better health and social justice" through a social science lens.

View entire SHAPES series

This is fascinating Jill, thank you. Your analysis of the reasons for limited archival material is worthy of a full study in and of itself — how colonial histories, organizational norms (swept desks–fascinating!), accountability processes (or accountability-related fear), resource availability, etc. influence the physical maintenance and order of health system documentation.

And even with digitization there’s no guarantee that archives will be in good shape: I’ve already faced issues with not being able to re-locate PDFs because of server issues or poor search functionality on MOH websites. There truly is so much need for LMIC historians to be supported (and for any HIC researchers to be overseen by LMIC project leads and good practice rules).

I’m so happy to see this article kick off the SHAPES article series leading up to HSR2020 in Dubai!

Thank you Jill. You have help bell the cat. Those responsible in LIMC for preserving historical facts just don’t understand or care. We just published an article on history of cancer in India. https://ascopubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/JGO.19.00048 , and just as stated by you, we had to collect many of the references from bygone colonial days from the British Library or Welcome collection.