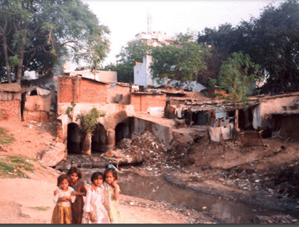

During my PhD coursework in 2013, I had my first (academic) exposure to the interconnection between human health, environment, and development. At the time, I had to make a field visit to the site where some of the 10,000 families residing in slums at the banks of Sabarmati River in Ahmedabad were rehabilitated – read violently evicted and relocated nearby a dump yard. The Sabarmati Riverfront Development Project started to curb pollution of the river from municipal and importantly industrial waste, but was implemented with strong violations of human rights including the right to life, right to shelter, right to work and earn a livelihood. As I reflect on the many more assignments I worked on thereafter, I gradually managed to unpack these interlinkages a bit deeper, ranging from the impact of indoor air pollution on women’s health, understanding the biomedical waste management system in India, to occupational health and safety hazards in the construction industry.

The latest Global Health 50/50 report on Planetary Health (titled ‘Gender Justice for Planetary Health’) helps to put my reflections further into perspective on: a) how gendered and disproportionate the impact of this development-induced environmental damage has been, further aggravated by the intersection of multiple inequities these population groups are already living with; b) how people from the most impacted population groups have rarely (read never) been consulted, or included in decision making spaces, which are typically dominated by elite and powerful men; c) people’s loss of trust in the state for recourse; and d) the need for integrating a gender justice lens in planetary health work, to mitigate the impact and regain people’s trust.

While the planetary health discourse has become more prominent over the past decade or so, featuring also numerous declarations and commitments signed at high-level meetings (including the Gender Action Plan at COP25 (2019) to strengthen the mitigation and response mechanism), action on the ground has been lagging far behind, especially by the countries, actors and organizations contributing the most to this climate crisis. You probably know who I’m talking about. At the same time, the climate emergency and other planetary boundary crises have gotten worse year after year, by now making the changes noticeable to even the ignorant ones. This week, for example, the world witnessed massive flooding in Dubai, earlier this month there was a lethal heatwave in the Sahel. Importantly, the cost of inaction is also shooting up fast.

Through its annual reports, Global Health 50/50 has been demanding more accountability from the global health organizations on gender equity. This (complementary) 2024 report does the same in the context of planetary health, by asking three critical questions: 1) do organisations’ planetary health activities integrate a gender lens; 2) do organisations sex-disaggregate the data they report on planetary health issues; and 3) who leads organisations active in planetary health?

The report reveals that gender-transformative action is remarkably absent from organizations working on planetary health (114 in total, of which 99 non-profit). Only 24% of the non-profit organizations (NPOs) in the sample have adopted a gender-transformative approach, 37% even failed to mention gender altogether. Interesting to note here, 38% of organizations had planetary health activities that respond to the specific needs of women and girls alone, with gender-specific programmes focusing on the traditional caregiving roles of women and girls. They thereby perpetuate the ‘feminization of obligations and responsibilities’ by placing the mitigation burden back on the shoulders of these women, without engaging men and boys or addressing other structural inequalities. This gender-specific approach also misses out on the specific needs of other genders and vulnerable population groups.

Further, the data collected and reported on planetary health must capture how sex and gender affect the health of men and women differently, by disaggregating data. The report shows that while 65 percent (63 out of 99) of non-profit organizations have published policy committing to data disaggregation, only 18 percent of these organizations have actually published any sex-disaggregated data.

Lastly, but most importantly, the assessment on leadership of these organizations shows a promising equal representation of men and women on boards of NPOs, but with abysmal (2.2%) representation from women from low-income countries. Moreover, among 921 board members (from the 60 organizations included in the Board review), 68 % are nationals of high-income countries, with 39 % as nationals of the US alone; only 4.5 % are nationals of low-income countries. And there are more discomforting stats in the report.

Reflecting on the findings, Prof Kent Buse, co-CEO of Global Health 50/50 stated ‘While we are delighted to see so many of the organisations in our sample engaging in urgent and much needed efforts on planetary health, we are somewhat concerned that they do not reinforce the same inequitable systems and reflect the prevailing structures of power and oppression that are driving our pressing environmental health crises.’

Women in Global Health’s (2023) She Shapes report highlighted that women leadership in global health has remained stagnant at less than 25 percent over the past five years, as compared with the (2019) Delivered by Women Led by Men report, while comprising more than 70 percent of the healthcare workforce. The specific needs and challenges of women delivering care and receiving care, as well as their voices are thus more often than not missing in the decision-making spaces. Within India, these statistics are even more disappointing, with women occupying only 18 percent of the healthcare leadership positions, in spite of the fact that 29 percent of doctors, at least 80 percent of nurses and midwives, and nearly 100 percent of ASHA workers are women.

By committing to women’s leadership in global and planetary health, collecting and reporting sex-disaggregated data, and adopting gender-transformative approaches, we will be better able to highlight and respond to the needs and lived experiences of communities deeply impacted by the actions and decisions made by people in power, largely men from the global north – thus challenging the structural inequities and addressing the root-causes of various forms of discriminations and oppressions.

The pandemic has shown the impact of gender equity in leadership. Through more diverse voices and representation, health and social care policies can be designed and implemented in an inclusive and responsive manner, reducing health inequities on the ground. Efforts like Global Health 50/50 ask vital questions in this respect, demanding accountability from organizations and countries on their commitments as well as actions taken towards achieving gender equity. But they also point to the way forward. As Kent Buse explained, ‘there can be significant power in uniting the efforts of the gender justice, health justice, and environmental justice movements. Together they can work to realise the indivisible rights to gender equality, to health, and to a healthy environment. Working together they will be more effective at dismantling systems that are harmful to planetary health than these movements working alone.’

This is even more important, dare I say, at national and local level. With important elections coming up in India, voters might want to keep this in mind!