Indonesia is in the middle of a bold health system overhaul. The government has been pushing for transformation since 2021 through six key pillars—among others aiming for strengthening primary care, digitizing systems, and ensuring equitable access across the country. On paper, it’s a big leap forward. With platforms like Satu Sehat, digital records and services are increasingly being linked. Telemedicine, e-referrals, and mobile apps are gradually making their way into public health centers and private practices.

But on the ground, the story isn’t always that smooth. Many frontline health workers—especially midwives and primary care doctors—are struggling to keep up. They’re expected to go digital, often without proper training, reliable equipment, or clear guidelines. Programs like Integrasi Layanan Primer (ILP), the integrated primary health care model from the Ministry of Health sound great, but in practice the picture is less positive. Who leads what? How do digital referrals actually work? What happens if the system fails?

As digital transformation sweeps in, one question keeps coming up: who’s really carrying the weight?

The promise of digital, the reality of the field

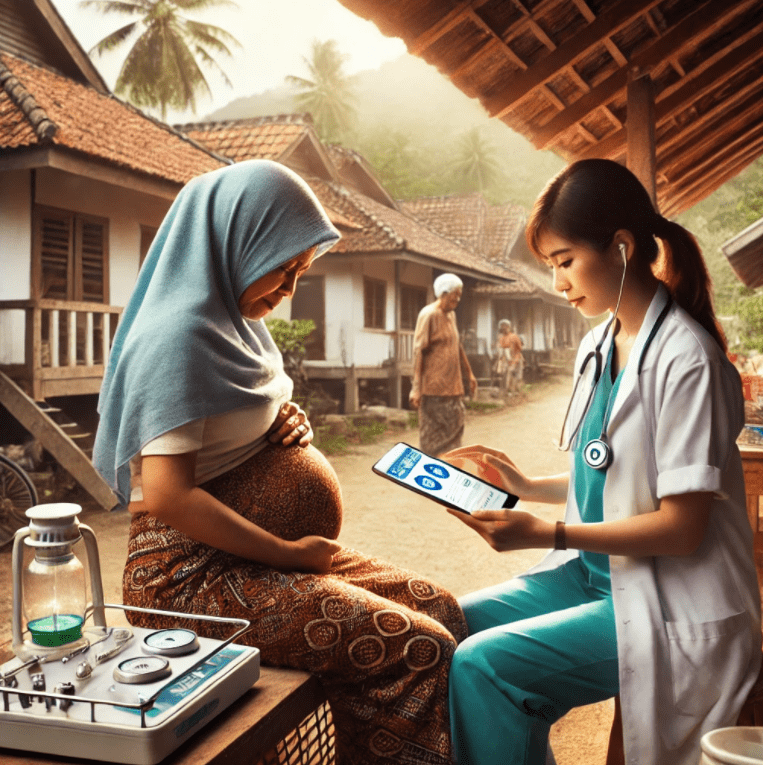

It’s not all gloom, though. In some districts, digital innovation is actually making a difference. In places like Lombok and Garut, for example, the SMART program makes use of wearable devices to monitor pregnancy risks. In areas without specialists, midwives can consult online. E-referral systems help detect complications early and improve coordination.

Yet, many health workers feel overwhelmed. Imagine spending the day attending to patients, only to come home and input data using your own phone, your own internet, sometimes well into the night. In remote parts, unstable electricity and a poor internet connection make digital work feel like a cruel joke. And so, for many, digital tools aren’t easing the burden—they’re adding to it. It’s not that they’re unwilling to adapt. The system just isn’t meeting them where they are.

Vague laws, blurred roles

Right now, Indonesia’s health laws haven’t caught up with its digital ambitions. Neither the Health Law (17/2023) nor the Midwifery Law (4/2019) clearly addresses accountability in digital care. If an e-referral fails and a patient suffers, who’s responsible? The midwife? The doctor? The platform?

This legal vacuum leaves frontline workers vulnerable. They’re already juggling expanded roles, now with added digital responsibilities—and no legal safety net. Some are even told their digital work doesn’t count toward official hours. All the effort, none of the recognition.

From digital burden to collective power

To make the digital health transformation work, we need to start with fairness and realism.

First, update the regulations. Clarify roles, ensure accountability, and protect health workers when systems fail. No one should have to work in uncertainty.

Second, embed digital literacy into professional training—not just how to use tools, but how to communicate digitally, collaborate across professions, and handle ethical challenges. Teams need to train together, not in silos. And yes, digital work is work. It deserves recognition and fair compensation.

Third, address infrastructure gaps. If the internet is unreliable, power cuts happen, or devices are outdated, then digital systems must be flexible. Offline options, phased rollouts, and designs that reflect local realities are essential.

Evaluating digital programs shouldn’t stop at user counts. We need to ask: do midwives feel more supported? Can doctors coordinate better? Are patients receiving care faster? Listen to the frontline—that’s where transformation either takes root or falls flat.

Yes, technology is important. But in the end, it’s people—not just apps—who make systems work. It’s people who drive change. That’s why we need a digital health system that’s not just smart, but humane. When midwives and doctors are involved from the start, backed by clear regulations, ongoing training, and fair recognition, digital tools can become a shared strength—not an invisible burden.

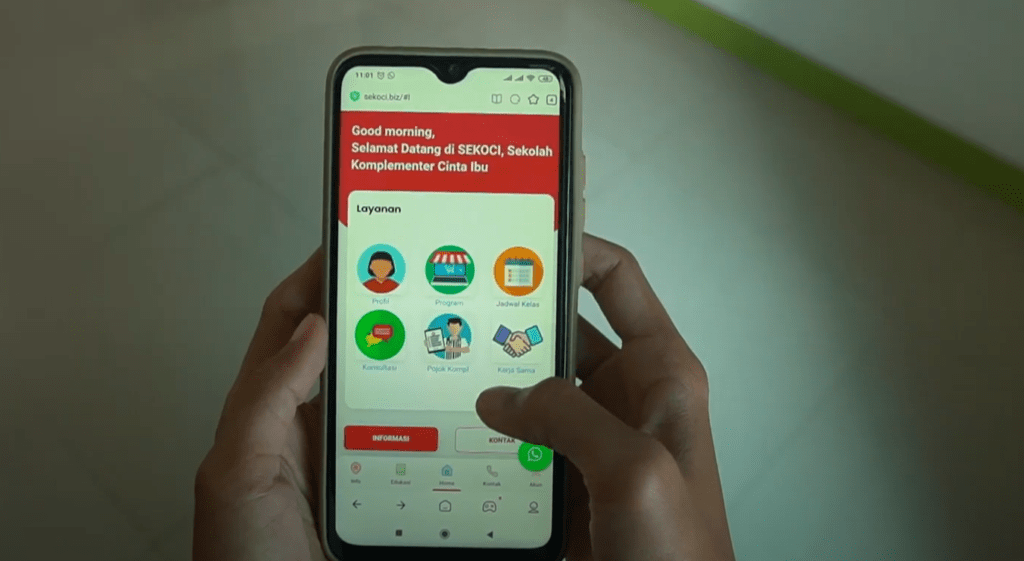

app example of maternal and child healthcare