“Care is an anathema to capitalism. Its virtues are capitalism’s vices. Its employment-rich foundation for wellbeing is capitalism’s productivity crisis. To a mainstream economist, employment intensity translates directly into low or stagnating productivity growth. The very thing, in that view, that is holding us back from the economic growth that we are so obsessed with. In neoclassical economics, wages follow productivity growth so capitalism condemns care workers to pitiful wages, insecure jobs, impossible working conditions. We forget that care (in its broader sense) is the invisible beating heart of our economy”.

This quote is part of a (panel) talk given by Prof. Tim Jackson during the recent “Beyond Growth” conference in the European Parliament (EP) ( 15-17 May 2023). His input during the panel on the “Care Economy” is amongst the most lucid analyses I have heard recently explaining the health and economic crisis we find ourselves in. It resonates with observations that United Nations (UN) policy strategies to invest in health employment and economic growth have not really made much impact. Despite all the applause for health care workers during the Covid19- pandemic there has been little structural investment in health jobs afterwards. Many countries revert to austerity measures, wage freezes and recruitment stops for permanent positions in the publicly financed health labour market. It is also a confirmation of the case made in a perspective written some years ago in which we argued that health and care workforce investment strategies should look beyond (sustainable and inclusive) economic growth, in terms of their main policy objective.

Beyond Growth

The Beyond Growth conference has been a major milestone in boosting (and broadening) the momentum for ‘a new economy based on sustainable prosperity, justice and sufficiency’. The conference was organized by a diverse coalition of EP members from across the political spectrum, and included panels with academics, politicians, policy makers and civil society representatives. Key arguments from the conference include the recognition that the mainstream economic paradigm based on the single- minded pursuit of GDP growth at all costs must change. Instead, public policies need to incorporate the complex dynamics of economic systems that are embedded in society and the rest of nature. Such models focus on societal wellbeing, and aim to undo the ecological damage done by (mostly) actors in high-income countries, increasingly overshooting biophysical planetary boundaries, at a breakneck speed moreover. In an open letter by 400 + experts, a set of key policy elements were proposed to transform economies in the European context. These include the need to implement Beyond Growth policies based on the four principles of:

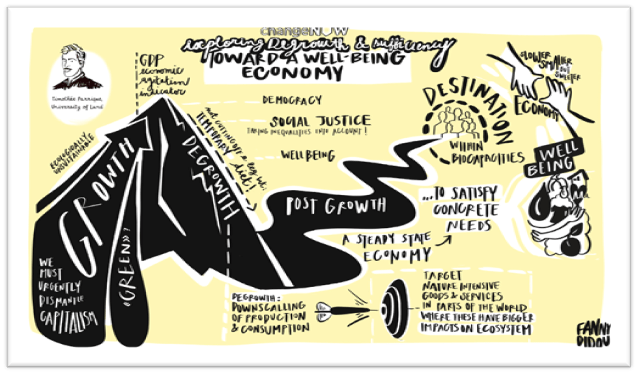

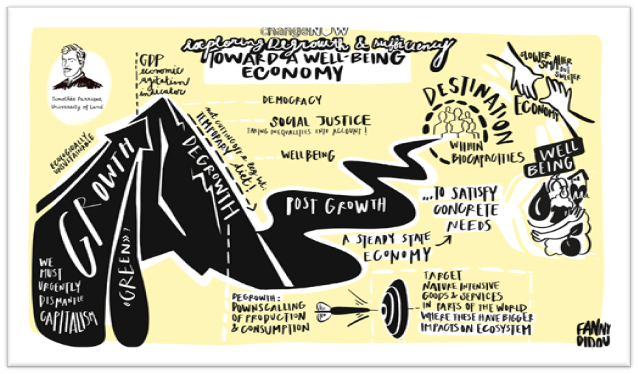

The question is then how to move forward from the theory, which is still hotly debated, to actions. Different normative and political visions exist here, with several arguing for active degrowth pathways for advanced economies in high-income countries, hereby undoing ecological degradation, and others arguing for a more ‘steady-state’ economy. Still others argue for more ‘sustainable, inclusive and green’ economic directions based on technological innovation, seeing space for further growth. The latter approach is prominent in the European Green Deal by the European Commission, which is an indication that there is certainly no European political consensus to move Beyond Growth, not even close. The political and societal debate on these various pathways will only increase, however, in the coming years and so it seems urgent to discuss how we relate to this key debate as health and academic actors.

Planetary health

So why does this matter from a planetary health perspective? So far the medical and (planetary) health community has engaged only to a limited extent with this contemporary political economy debate. Recent exceptions include the WHO Council on the Economics of Health for All, The People’s Health Movement and EuroHealthNet. Investing in public health structures, broader care systems, social protection and equity have become key policy considerations in post-growth circles. The (mainstream) medical and health community isn’t very involved so far, though, in post-growth economics research and practice. A recent review in Plos Global Public Health suggests that this may be due to a potential tunnel vision on climate change and health. While climate change is widely recognised as “the greatest threat to public health this century”, the medical community tends to focus on Co2 emissions, the impacts of climate change on health, and the adaptation by resilient and sustainable health care, instead of going for a more holistic assessment of economic structural determinants and systems of (historical) oppression that intersect with health, care and its outcomes. In addition, various current and future global health risks, including potential pandemics, have probably also led to the further securitization of health whereby nowadays’ focus lies on biomedical prevention, preparedness and response to health threats. Such an orientation may distract from the need to reclaim comprehensive public health capacities and structures.

Another elephant in the room is the fact that the health care sector itself is amongst the fastest growing economic sectors globally, often growing faster than GDP itself. Do note though that this is not the case for many lower income countries. In Germany, in 2021, health expenditure accounted for 13.2% of GDP and has reached about 500 billion euros in 2022. In such a fast-growing service sector there are many commercial and private interests, and investments in health care. European governments (with a few exceptions) falter in regulating or protecting the public orientation and accessibility of these health and broader social protection systems. This is not new, but the result of a decades-long neoliberal policy agenda. As a result of both public and private actors furthering commodification, individualization and profit-orientation in health care systems in European (high- and middle-income) countries, these have become more medicalized, and are actually moving away from being care-centred. They risk to become dis-embedded from contextual social and care structures and actual people’s needs. This leads to a phenomenon known as ‘uneconomic growth’ . This occurs when increases in production come at the expense of resources and well-being that is worth more than the items made. In health care this becomes visible when the social and environmental costs of expansion of the health system actually outweigh the benefits. A considerable amount of current investment in health care is indeed of low economic, social and ecological value, and may even do harm. For instance, studies indicate that some 10–30 % of all health care activity in middle- and high-income countries might amount to overuse, which is a combination of overtreatment, overdiagnosis, low-value care and pharmaceuticalisation.

Health justice across disciplines and sectors

What is to be done? In addition to (merely) focusing on the intermediate and proximate individual, medical and ecological risk factors of health, planetary health actors should also engage with actions targeting the structural, commercial and political determinants of ill health, disease and inequity. This is where interdisciplinary and intersectoral cooperation with the ‘beyond growth’ economics community makes much sense. The health community could collaborate on the four policy principles of biocapacity, fiscal fairness, wellbeing for all, and citizen assemblies and make them relevant and (try to) apply them on the health sector itself. So far, the planetary health community has mainly focused on ecologically targeted actions such as One Health approaches and sustainable health care. There is however a need to urgently engage with broader, more politically oriented initiatives, involving also the 3 other post-growth policy domains. This requires health actors to be more explicit about their normative positions, including on what the (urgent) economic transformation actually implies for the health sector itself.

Engaging with localized ‘care economies’ and informal care structures could be an entry-point as feminist and degrowth visions for care offer possibilities to develop “global commons” beyond the marketized health economy and nurture human flourishing within planetary boundaries. Reclaiming comprehensive primary health care, in line with the spirit of the WHO Alma Ata Declaration of 1978 would also be a good basis for action. But these investments in health and care will only work if we also “degrow” low-value health care and put limits to medicine itself.

Graphic image from Timothée Parrique’s twitter account capturing his keynote on Post-growth policies at ‘ Change Now 2023’