In recent years, the world has witnessed an alarming increase in the numbers of internally displaced people (IDPs). Today, IDPs represent the majority of the world’s displaced, with 71.1 million IDPs globally at the end of 2022. Of these, 62.5 million had been affected by conflict or violence and 8.7 million by disasters.

Research suggests that IDPs tend to experience worse health outcomes than refugees who attract more attention for research and funding. In addition, while IDPs in rural settings have rightly received attention, the challenges faced by their urban counterparts seem to be overlooked.

Mali – a country with a population of 23 million, has become an epicenter of civil conflicts, with more than 346 000 IDPs in 2020. Most IDPs fled toward the southern cities of Mali, where they settled with host families and in informal camps. Over the last ten years, the country has faced a complex challenge of integrating urban IDPs into community-based primary healthcare (PHC), leveraging the transformative spirit of the Bamako Initiative . As a reminder, the Bamako Initiative, launched in Mali in the late 1980s, champions community involvement, financial sustainability, and accessibility in healthcare delivery.

Mali’s health system & health risks for IDPs

Public spending on health is low in Mali. In 2019, less than 6% of the government budget was dedicated to health, far below the Abuja target of 15%. The government’s share of country current health expenditure can be considered as limited ( e.g. 34.4% in 2020) , especially within the context of external aid limitations and increasing poverty prevailing since the coup in 2020. So, the current situation is one of poor public health infrastructure, a shortage of trained health workers, and geographical and financial barriers that make it difficult for many Malians to access healthcare, especially within the context of external aid limitations and increasing poverty. Health indicators in Mali are among the lowest in the world, with high maternal (325/100 000) and under-five (97.1/1000) mortality rates, and a high prevalence of infectious diseases such as malaria.

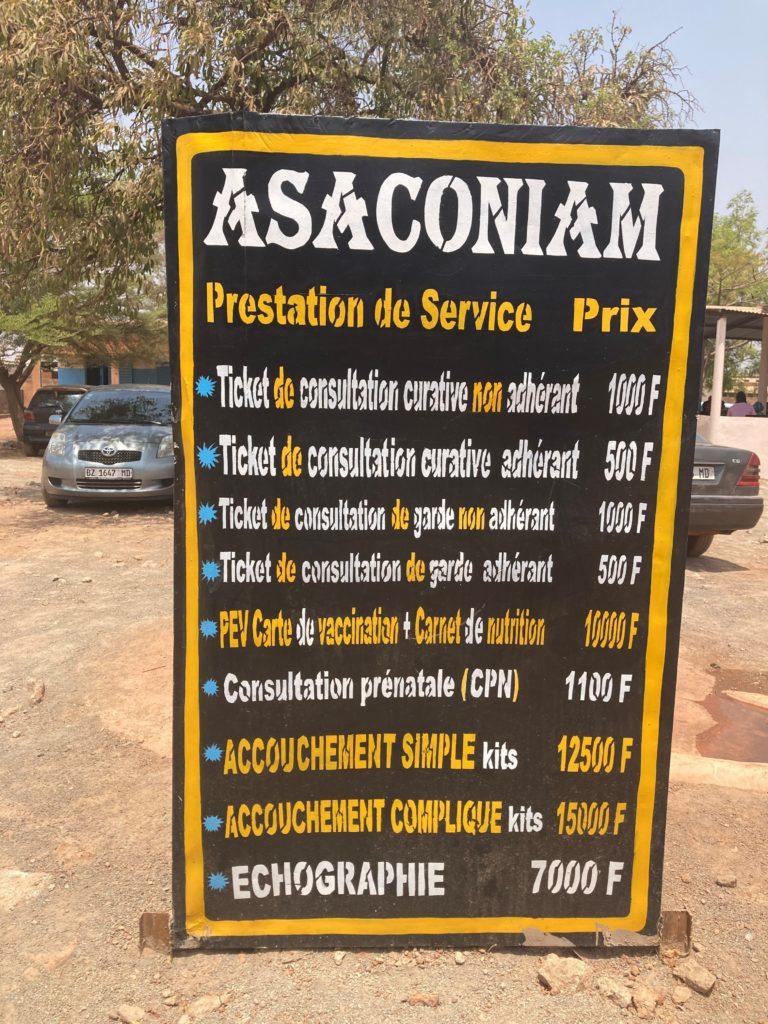

Primary healthcare forms the foundation of Mali’s health system. Community health centers (CSCOMs) are usually the first point of contact with the health system for most individuals. They are also non-profit organizations managed by a user association, the Community Health Association (ASACO). These are composed of a dispensary, a maternity ward, and a pharmaceutical repository. Community health workers play a crucial role in providing basic healthcare services and co-exist with traditional healers.

Integrating IDPs into community-based primary health care is one way to bring medical services closer and ensure that IDPs, who often lack reliable transportation and face financial constraints, have easier access to essential services.

Indeed, with many IDPs moving into urban areas, overcrowding and poor sanitation can fuel communicable diseases, placing both IDPs and the host communities at risk. In addition, the trauma of displacement, separation from family, and exposure to violence can have severe psychological impacts on IDPs. Furthermore, malnutrition poses a severe health risk among urban IDPs, especially among children, leading to long-term consequences on physical and cognitive development.

The need for integrating urban IDPs in Bamako Initiative-driven PHC

Integrating urban IDPs allows for tailoring care to their beliefs and practices, fostering trust and cooperation. Community-based healthcare facilitates comprehensive care, and also plays a role in addressing the psychosocial challenges that often accompany displacement. Proactive disease prevention measures ensure that both IDPs and host communities are safeguarded. Most importantly involving IDPs in community health initiatives may empower them to take ownership of their well-being, fostering a sense of belonging, and promoting social cohesion. Finally, integrating IDPs into local healthcare networks may enhance data collection, enabling authorities to accurately assess healthcare needs and allocate resources effectively.

However, unlocking the full potential of integrating urban IDPs into Bamako Initiative-driven community-based PHC requires a symphony of collaborative efforts among various stakeholders: governments to prioritize healthcare equity and enact existing health and policies; urban communities to play an active role in ensuring healthcare services cater to the specific needs of IDPs; and non-governmental organizations and international partners to provide vital resources, and share technical expertise.

In a world marked by multifaceted crises, bottom-up research and policymaking taking into account urban IDPs and their host communities while tackling the complexity of their environment, is key to ensuring that healthcare is inclusive, accessible, and adapted to those who are on the run in their own country.

Price list of the CSCOM of Maniama (the closest CSCOM of Yirimandio camp, at the periphery of Bamako) where IDPs have to pay double the price because they are not affiliated.