The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that there will a shortage of at least 18 million health workers globally by 2030 if drastic measures are not put in place to create health sector jobs and improve the working conditions for health workers. The Africa region has an estimated additional requirement of 6.1 million health workers by 2030. At the same time, paradoxically, the region is also likely to have at least 700,000 trained health workers who will be unemployed due to inadequate investments in health workforce employment and working conditions.

The current situation is likely to fuel migration of skilled health workers seeking job opportunities in developed countries and Africa will thus face even greater challenges in retaining its skilled health workforce.

Now enter the outcome of the just concluded UK elections.

As you might recall, during his recent election campaign, Prime Minister Boris Johnson pledged to recruit 50,000 nurses, 6,000 doctors and build 40 hospitals across the country if elected. And sure enough, the election culminated in a landslide victory for the Conservatives Party, resolving – for better or for worse – the parliamentary deadlock that had stalled the conclusion of the UK leaving the European Union (EU), worldwide known as “Brexit”.

Since the Brexit referendum in mid-2016, various uncertainties have triggered many of the over 65,000 EU migrant health workers in the English National Health Service (NHS) to consider returning home (or to other countries) while the number of new EU health workers entering the UK has plummeted to an all-time low. For instance, in 2015-16, prior to the Brexit referendum, 19% of nurses who joined the NHS were from the EU. By 2017-18, this figure had plummeted to 7.9%. With Brexit now more certain than ever, and set to happen sooner than later, the NHS will most probably increase recruitment of health workers, especially nurses and doctors, from outside the EU. What does this hold for Africa’s health workforce crisis, given its ‘migration-ready’ doctors and nurses?

African health workers in the English NHS – July 2019

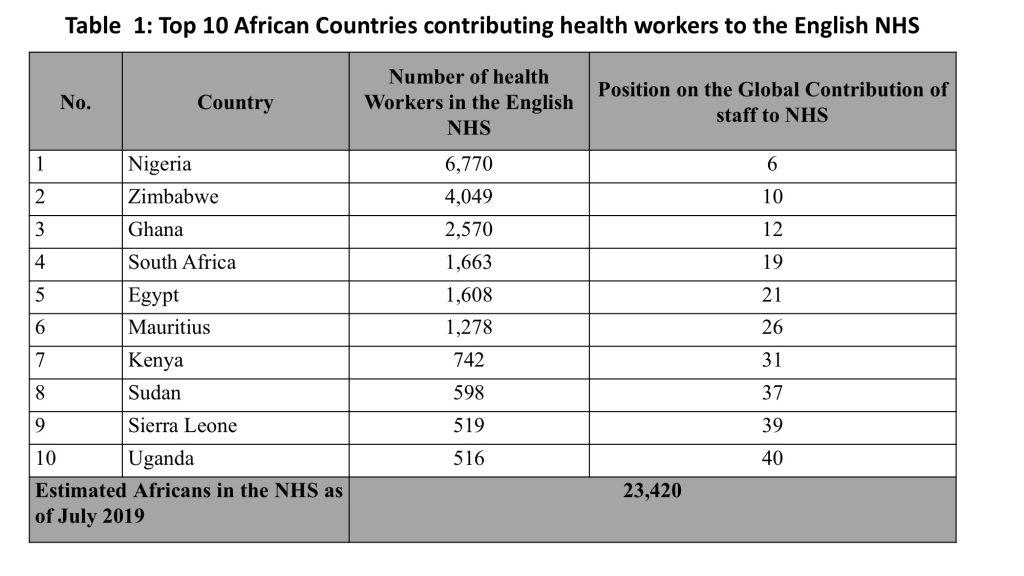

On the back of WHO’s World Health Report of 2006 and the Global Code of Practice on International Recruitment of Health Workers, UK had listed several developing countries (including 48 from Africa ) from which it should not be actively recruiting health workers. This notwithstanding, statistics made available to the British Parliament in July 2019 revealed that three African countries, Nigeria, Zimbabwe and Ghana together contribute at least 13,246 health professionals to the English NHS. Africa as a continent contributes no less than 23,420 health workers to England alone, 87% of whom are from only 10 countries (see table 1 for details). In a BBC news item, NHS employers reportedly said most of these individuals came to the UK “… independently, on their own initiative without encouragement or support from the NHS.”. Nonetheless, available data show that:

In fact, even without the NHS employers actively recruiting from Africa, 6 out of the top 30 source countries globally for NHS staff are African countries (see table 1).

Potential impact of Boris Johnson’s victory

With a merit-based points system of migration in the offing and 50,000 nurses as well as 6,000 doctors to be recruited (as promised by Boris Johnson), many will probably come from Africa, especially from Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Ghana and South Africa where the nursing education system is quite similar to the UK (these countries are already the top 4 source countries for nurses in the UK from Africa). With the number of EU nurses and doctors registering in the UK dramatically declining, chances are that even if NHS employers maintain their stance of ‘no active recruitment’ from Africa, the influx of nurses and doctors from Africa to the UK will surge after Brexit through their ‘individual efforts’. In Nigeria, Ghana and Zimbabwe, there has been a recruitment drive, mostly by private companies since the Brexit referendum in 2016. From all indications, this trend may gain further momentum and the possible effects in Africa are that:

As more than 65% of health workers in Africa are nurses and doctors who are at the centre of delivering UHC, the aforesaid is food for thought for governments and health policy actors in Africa. Surely, with the Sustainable Development Goals and Universal Health Coverage firmly on the agenda of African countries, the time to invest in employment and decent work for health professionals is now!

#InvestInTheHealthWorkforceNow!

Thank you for this interesting blog. It’s a good example of the systems effects of events half way across the world. The promise of an extra 50,000 nurses caused quite a lot of debate here in the UK and so the claim was examined by the BNC’s More or Less programme which looks at “the numbers and statistics used in political debate, the news and everyday life”. The radio programme at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m000bx15 (listen to the first 7 minutes) provides an explanation which includes the issue of staff retention, and – not surprisingly – international recruitment. Of particular interest to workforce planners – and possibly politicians!