Rachel Thompson is a researcher currently based at a UK think-tank. In this blog she shares her personal reflections from the recent Prince Mahidol Award Conference (PMAC) on the political economy of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), considering the wider implications for our understanding of Global Health.

Last week the elite of Global Health gathered in Bangkok for the Prince Mahidol Award Conference. This annual invite-only event attracts Global Health leaders from around the world, as well as practitioners and researchers from South East Asia. While previous years have covered infectious disease, UHC, equity (i.e. the usual), what was special about this year was the original theme, The Political Economy of NCDs, making it the first Global Health conference to address explicitly political economy – an exciting prospect.

Yet as the conference drew to a close I was overwhelmed with the same familiar feelings of frustration and hypocrisy that I have got used to at Global Health events. I know these sentiments are echoed by many friends and colleagues. My hope is that by publicly articulating my feelings (in more than 140 characters), we can begin to help transform our disappointment, frustration and anger even, into something more useful.

DISCLAIMER: I am hugely grateful to the ever-impressive PMAC Secretariat, and all those who worked so hard to make this conference a reality. This is not meant as a critique of anyone in Thailand involved. However, by design, PMAC delegates power to the Organizing Committee, made up of the co-hosts (see below), described by Margaret Chan during the conference as a “who’s who” in Global Health. This blog is not aimed at anyone in the PMAC Secretariat, but it is aimed at everyone in Global Health – and especially those associated with these organizations.

PMAC co-hosts: the “who’s who” of global health

The political economy of PMAC

Leading up to the event, over the last nine months I had the opportunity to participate in the organization of PMAC at various planning meetings. I soon realized that what I was observing in these meetings was a microcosm of Global Health. Around the table, representatives from all the big players; speaking freely, but also defending their institutional perspectives, and protecting their own Global Health ‘territory’.

As conversations digressed from the minor matters of the conference sessions, to the mega matters of how PHC and UHC are related, I saw that this opportunity was in fact a unique window into the political economy of Global Health: how the unbalanced distribution of power and resources play out, to amplify some perspectives over others, ultimately to shape the agenda and control outcomes.

Although in this case the outcomes were fairly benign – the structure and content of a conference – the discussions were fascinating and, while being under Chatham House rule, I cannot share details of who said what, I can share my critical reflections on what I saw and heard. Combined with my experience (and participant observation) at other Global Health fora, below I outline what I have learned about the political economy of NCDs, and of Global Health.

Civil society is being systematically disempowered

In political economy terms, the funding organizations civil society organizations (CSOs) rely on use their resources and material power to control what activities are and are not funded. To paraphrase the proverb, it is hard to bite the hand that feeds; especially when that hand has paid for your airline ticket and is feeding you a three course dinner at a five star hotel. While it is important to have a seat at the table, that table is not an even one and power asymmetries perpetuate. Voices are heard and respect is given, but it is a bitter sweet respect that leaves a sour taste in my mouth.

In the world of NCDs beyond PMAC, civil society are being steered towards certain actions over others. CSOs are being offered funding and partnerships that focus on treatment and access to services. For all organizations, funding to work on the prevention of NCDs is limited. Funding to work on the drivers of NCDs (including the commercial determinants) is even harder to come by. All these issues reflect broader challenges around partnerships that the SDG era presents in its opening of the floodgates to the private sector.

The conflation of treatment and prevention may be problematic in tackling NCDs

Within Global Health, the issues around NCDs are being framed in terms of treatment solutions. Solutions that, for example, often involve public private partnerships to accelerate access to pharmaceutical products. This issue was evident in the UN General Assembly high level week (leading up to the 2018 High Level Meeting on NCDs), where only four out of over 50 Global Health side events mentioned prevention. Although in contrast, prevention was very clearly on the agenda at PMAC, the discussions soon returned to circular debates over engaging with “health harming” industries such as food and alcohol. This clip illustrates the situation at PMAC, where civil society (the People’s Health Movement and NCDFree) felt they had to interrupt the plenary to have their voice heard, to help support the brilliant panelist Kwanele Asante’s points. My analysis: if, as to quote Rhea Saksena, civil society are in “an abusive relationship with industry”, Global Health is an uncomfortable third wheel in this long-term relationship between Public Health and trans-national corporations.

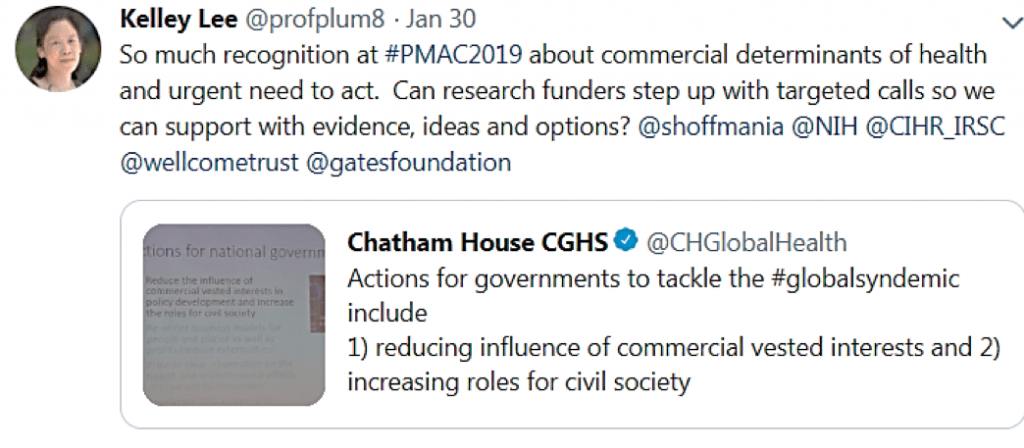

The commercial determinants of health are at the top of everyone’s intellectual agenda – but action is not being funded

The most energized and

This brings me to a tautology that I think is worth repeating:

Public Health and Global Health are not the same

Public Health being “the art and science of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts of society” (Acheson, 1988; WHO). Global Health, here, being the self-identifying group of institutions, actors and individuals who work on issues that affect global public health (my own working definition). In NCDs, arguably more than for infectious disease, this distinction needs to be maintained. While in reality it may be hard to separate the two endeavors, conflating them conceptually is an issue. Both are political, however, Global Health – as a product of a certain time and place – cannot be taken out of the global political (and economic system) that created it. Public Health is here to stay, Global Health may not have the same longevity.

Global Health is part of the neoliberal global political economy

The global political economy is one dominated by the ideology of Neoliberalism, which places the individual and free-market at the centre. As I suggest above, Global Health is a product of the Neoliberal era (Public Health is not). While changing the rules of the economy is clearly beyond the remit of both Global and Public Health, failing to situate our endeavors within this bigger context is a problem. Once we understand Global Health as inseparable from Neoliberalism, we can begin to get to the root causes of why so much of the world are being “left behind” from global goals. To ignore its influence is to deceive ourselves and the people we are trying to serve.

Once we understand Global Health as part of a system that has increased global inequalities and inequities, it seems strange to expect it to do the opposite – to “reduce inequities” e.g. as part of Agenda 2030’s leave no one behind pledge. This is the paradox at the heart of my frustrations with Global Health.

The appropriation of ‘political economy’ by Global Health actors could distract from understanding the political economy (and underlying issues of power) within Global Health

Finally, there is a danger that by holding a conference on political economy, by self-congratulating ourselves on seeking to address the issues of power and inequality in NCDs, a box is ticked and we move on. There is also a danger that the appropriation of the term by powerful players is a dangerous move. We need more political economy analysis of Global Health and its institutions. But who will fund it? Who will publish it?

The aim of PMAC was to: “identify major bottlenecks, root causes and propose solutions at national and global level to accelerate implementation of NCD prevention and control”. While it certainly fulfilled the former objectives, unsurprisingly, solutions to root causes were not forthcoming. This raises the question: should an elite UN dominated Global Health conference be dabbling in political economy? I am not so sure.

Moving forward…

To conclude, I offer a few tentative suggestions for those who are also frustrated with the current status quo in Global Health.

1) Let’s leave Global Health to do its business: to protect us from pandemics, to fight infectious disease, to find the cure for cancer, to work towards Universal Health Coverage, to give us all the data it can generate.

2) Let’s leave the UN system to its work with member states, in safe-guarding norms, and aspiring to global goals.

3) In the meantime, let’s use the data Global Health generates more smartly – to show what is not happening as well as what is. And to use more political economy analysis to help show why.

4) Let’s dumb down the messages around NCDs, so that members of the public all over the world can understand the issues and causes of injustice. Let’s tell the stories behind numbers in ways that people can understand, communicated in forms they utilize (clue: not case studies!).

5) Finally, and most importantly, let’s be inspired by people like Thailand’s Dr Suwit, to be champions, to not give up on what we believe in (for me, gender equality, equity and social justice).

But let’s also be realistic: Global Health is great for measuring things and improving health security; it is not necessarily the right place for people who want to tackle injustice, and change the world in the many ways it so urgently needs changing.

Hi, Rachel: I also attended the PMAC meeting. I work with Latin American countries to help advocates in specific countries join together to develop advocacy strategies to advance policy change in their countries. As I said at the meeting, we are drowning in reports and what you probably would call “Global Health” outputs, while at the level of advancing policy change in specific countries, we work with little or no resources. As thankful as I am for whatever financial support we do get from international sources, it is many times impossible to do the work that needs to be done to advance policy change, promote health equity and improve health locally.