The Consortium of Universities for Global Health (CUGH) 10th annual meeting took place in Chicago (8-10 March) under the theme “translation and implementation for impact in Global Health”. This was the first time I attended this conference; I left feeling hopeful yet remained confused on multiple fronts. But, before we get into that, two things:

First, a caveat. There is a reason this was the first time I attended the annual CUGH meeting. I am, quite honestly, often skeptical about anything labelled as “global health”. As someone who is interested in studying determinants of the health of the global population, I am often baffled with the lack of consensus on what the field of global health encompasses in practice. This is in spite of the many efforts, examples include the work of Koplan et al, Abimbola, and Taylor, to establish a clear definition in the literature. In practice, at least in my limited experience, the term ‘global health’ is often used to describe unidirectional initiatives (often from HICs to LMICs) dictated by power imbalances—geopolitical, monetary, or other forms of power—and constructed around the concept of the ‘haves’ giving to the ‘have nots’. In short, not all that different from its predecessor, ‘international health’. I think that without addressing these imbalances, those working in “global health” will not be able to address the emerging threats facing the global population in this century. My reflection should be taken with that understanding in mind.

Second, a disclaimer. I really enjoyed the conference. In addition to the wide range of timely topics discussed, it was clear that the organizers went out of their way to embody values of equity and diversity. The conference itself was global in terms of representation—with participants from over 50 countries and a diverse set of presenters and moderators (it was a bit heavy on presenters from the US but that is understandable given that the conference was held in Chicago).

The Great Debate

Back to the content of the CUGH annual meeting. This year, the proposition of the conference’s ‘Great Debate’ was “The field of global health should prioritize existential threats, including climate change and environmental degradation, over more proximate health concerns” with Stephen Luby arguing for the motion and Agnes Soucat arguing against it. Many of the conference attendants—including the moderator and the two discussants—noted in their remarks that creating an either/or distinction between existential threats (examples used during the debate included climate change and nuclear threats) and proximate health concerns (this was not clearly defined in the debate but the context implied by the term meant, more or less, current areas of interest for the field of global health) would be artificial. The debate ended with the two discussants making a similar argument—although with different framing—that the two goals are not contradictory, can work in conjunction, and feed into each other (Although, for a while there, Soucat drove the discussion towards the direction of individual versus collective responsibility). By the end of the debate, about half of the attendants voted for the motion and half voted against it but the general consensus was that the field did not need to make a distinction between priorities.

At first, I did agree with the apparent consensus. After some more reflection, however, I think that the question was actually well phrased and that it is perhaps the single most important question to ask in global health right now. Further, the split in votes does reflect the current state of global health as a field unsure of its future direction. While both goals reveal a concern about the health of the global population, embracing for one or the other can fundamentally determine how we frame global health as a discipline, what issues fall under the jurisdiction of global health “actors”, and, more importantly, who we consider to be global health actors to begin with.

Choosing proximal health concerns (as framed in the debate) as a guiding vision for the field is a noble goal that fits the business-as-usual approach we currently, overwhelmingly, adopt in global health. On the other hand, embracing existential threats as a key driver for global health priorities would require a bold shift in the field. It would mean broadening the scope of the discipline, becoming more “political”, and engaging stakeholders who are not currently being considered as global health actors. That is not to say that current proximal concerns (say UHC, NCDs, …) do not require a more “political” approach. But, embracing existential threats as a key target for global health requires making sweeping and most likely unpopular and uncomfortable decisions. It means a deeper (and more radical) engagement on issues such as the structure of the global economy. For example, adopting such vision to global health would imply that adding a chief economic advisor to the structure of the WHO’s HQ is not a far-reaching question asked on twitter but rather one of the most logical steps to prepare for the future threats facing the health of the global population. To his credit, Luby tried to make a similar argument multiple times during the debate.

One thing to keep in mind, as the field continues to search for its purpose, is that while the debate was indeed a good intellectual exercise, we might not have the luxury of being able to continue debating the proximal vs existential for much longer. Soon, even the proximal may become existential (e.g. biodiversity implosion and climate change) or is it the other way around? In fact, the ability to define what constitutes a global priority might not be in the hands of “global health experts” much longer but rather in the hands of those who will suffer the most from what we call now existential—also often (still) implied as distal—threats (for an example, look no further than the global movement of youth climate change strikes). Importantly, if we continue with our business-as-usual approach to global health, we might very well end up unprepared for the looming future global (health & other) threats.

CUGH 2019 Honorable mentions

China as a Global Health Actor

One of the sessions at the conference was dedicated to showcase the role of China’s partnerships with LMICs to improve health outcomes. I was particularly intrigued to see how the session unfolded as China itself (still) has a long way to go when it comes to improving a number of health indicators and outcomes. Acknowledging China as a global health actor means, in principle at least, more discussions about south-south collaborations. However, the rising geopolitical power of China—in Africa, South-East Asia, … — (not the least via the Belt and Road Initiative) means, again, a power imbalance in these partnerships. The presentations, however, were encouraging. Multiple presenters from academic institutions (e.g. Tsinghua University, Fudan University, and Wuhan University) in China made it clear that they, also, are still working on what it means to be a global health actor. Many highlighted the need to first define what global health means and what a successful partnership in global health would look like.

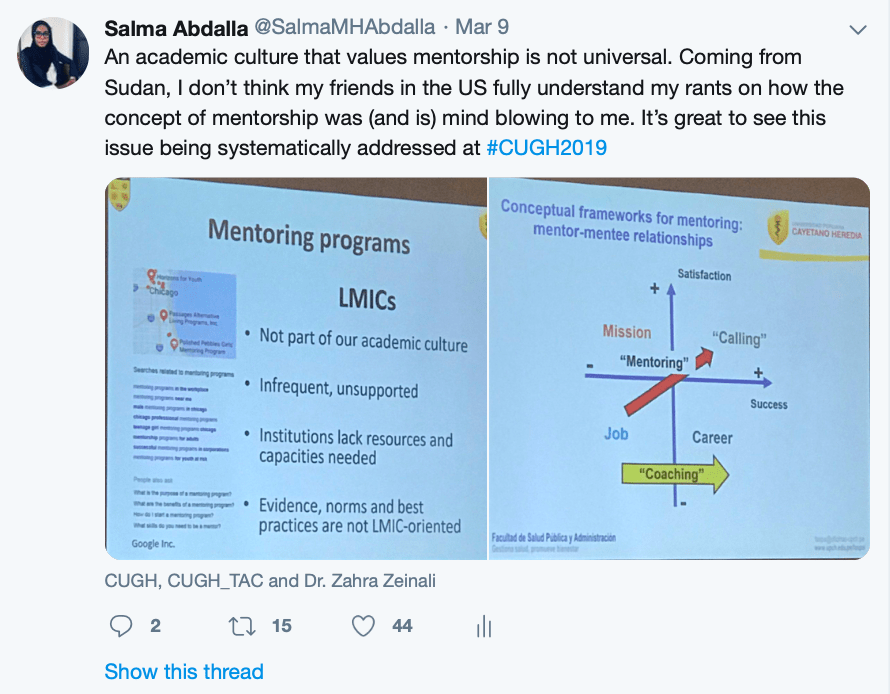

Mentorship in LMICs

I’m mentioning this session because it focused on a topic that is dear to my heart. As you can see from a screenshot from a live-tweet below, I was ecstatic to see that the issue was systematically addressed at the conference and (hopefully also) beyond.

Medical Humanities in global health

This session gets an honorable mention because it aimed to conceptually address the current power imbalances in global health with a nod towards the emerging topic of decoloniality in health research and practice. I would argue that at least a basic training in humanities is essential, yet it’s foreign, to many of us who are working in clinical medicine/public health.

Short-term placements in global health

Multiple sessions aimed to address the ethics of short-term placements; a popular practice by global health educational institutions in the west. Such placements are often in located in LMICs. The global community is increasingly acknowledging the, often, unintended harmful consequences of such placements on local communities. While none of the sessions directly addressed the inherent power imbalances driving these placements, they definitely highlighted the ethical issues that need to be considered as global health institutions in the west continue with the practice.

Final thoughts

To be honest, a week after the CUGH meeting, I’m still puzzled by what we mean when we say global health. I do not think anyone at the conference would disagree with Koplan et al’s definition of global health as “an area for study, research, and practice that places a priority on improving health and achieving equity in health for all people worldwide. Global health emphasises transnational health issues, determinants, and solutions; involves many disciplines within and beyond the health sciences and promotes interdisciplinary collaboration; and is a synthesis of population based prevention with individual-level clinical care.” At least I hope not.

But at this point in time, does global health, in its current shape and with the current political economy of global health actors, does what it aims to do? How do we operationalize such definition? Huge threats to the global community such as climate change will surely have an effect on the health of the global population, already now but certainly even more so for future generations. So, is global health—in its current form—ready to face such threats? Currently, global health seems to focus on ‘mitigating’ the worst aspects of our world while not really taking on the challenges we face in the 21st century in a more substantial and transformative way. Maybe Koplan’s definition doesn’t pay enough attention to the health of future generations?

Another important question to ask is what constitutes empirical evidence that could drive the field of global health? How do we identify and measure “global health priorities”? In other words, what type of work do we feature as global health research?

At this conference, the answer was overwhelmingly: research conducted in LMICs, regardless of the topic. Such focus is fine—but it does reinforce the narrative that, at least empirically, global health remains a fairly unidirectional discipline. Such emphasis is also a bit weird in the—supposedly “universal”—SDG era. Further, I wonder whether current global health curricula adequately prepare us to address, at least some of, these emerging transnational (and more existential) threats.

The emerging health challenges facing our global population require taking quick steps towards defining whether global health is truly concerned with the global population (including future generations) or whether it remains, deep down, an extension of international health. No matter the direction, there is much work to be done to create a discipline that is courageously devoted to address drivers of health in the global population—now and in the future—conceptually, methodologically, and in practice (be it global health or something else).