Each year, the global health calendar (as graphically summarized by Kent Buse on Twitter recently – here’s part one) begins with the Prince Mahidol Award Conference (PMAC) in Bangkok – together with the WHO Executive Board Meeting in Geneva, of course. Under the patronage of the Thai royal family, PMAC honors Thailand’s Father of Public Health and is held alongside the awarding of public health’s ‘Nobel Prize.’ Since 1992, there have been 46 public health laureates, which include global health rock stars Michael Marmot (forever SDH champion), Anne Mills (mentor to many Thai health systems specialists), Peter Piot (director of the London School), and Jim Yong Kim (who just left the World Bank for a private equity firm).

While PMAC has been running since 2007, this is only my fourth time to attend this event. (See my blog about PMAC 2015 here.) Every year, this by-invitation-only conference revolves around a specific theme – and for 2019, it was the political economy of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs). This year’s opening speaker, Harvard professor Michael Reich, lauded PMAC for being the first global health conference to include “political economy” in its title. Inspired by Harold Laswell’s definition of “politics” – “who gets what, when, and how” – Prof. Reich offered a simple definition of “political economy” for PMAC’s audience – “how the allocation of political resources and economic resources affects who gets what, when, and how.”

While the focus of the conference was NCDs, one can’t help but use the same lens to understand PMAC itself as it unfolded. Recently, there has been so much buzz about global health conferences – from declined visa applications among Global South delegates to lack of representation in panels based on gender, nationality, and intersectionality. While a full-blown political economy analysis of “who gets what, when, and how” merits a longer academic paper (though Chatham House’s Rachel Thompson did a good job in a recent blog, drawing from her insider perspective), let’s do a quick-and-dirty description of “who gets invited, who doesn’t, and so what” – PMAC style. Here’s my part-ethnography, part-Twitter analysis:

Voices old and new

One of the biggest annual reunions of global health’s ‘Who’s Who,’ PMAC 2019 was more than a venue for political economy discourse; it was a sneak preview of global health’s political economy in action. As expected, the World Bank’s Tim Evans was there not just for one but two plenaries. Meanwhile, I’m not sure if anyone noticed the absence of Svetlana Axelrod, WHO’s assistant director-general for NCDs, though there was a sprinkling of WHO staff working on NCDs from Geneva and regional offices.

Of course, this is the time to shine for Thailand, as its hardworking public health specialists showcased the country’s impressive achievements from its Universal Health Coverage program to Health Promotion Fund. Various UN agencies, financial institutions, foundations, and nongovernmental organizations, especially those devoted to NCDs (such as the new Bloomberg-funded initiative Resolve to Save Lives led by former US CDC head Tom Frieden), were present as well. Due to Thailand’s location, PMAC also invites seasoned and emerging public health specialists from Southeast Asia – myself included.

While Richard Horton was sorely missed, the Lancet’s imprint was very much felt through the newly-launched Syndemic Commission linking obesity, undernutrition, and climate change. (These Lancet commissions are another agent of global health policy worthy of political economy analysis.) Meanwhile, as one of Global South’s most passionate planetary health advocates, I was elated that PMAC also had a few of us ‘voices in the wilderness’ talking about the more upstream environmental (non-behavioral) drivers of NCDs. (Dear Thai friends, here’s my suggestion for PMAC 2021 theme – “Planetary Health: A New Paradigm for Global Health.” Let’s do it before it’s too late!)

In the spirit of much-invoked and eternally-fuzzy ‘multisectoral collaboration,’ PMAC also invited a few representatives from the ‘industry’ as well. One notable guest came from the International Food and Beverage Alliance, who during the opening panel urged the audience to stop viewing the food industry as a ‘monolith’ and instead begin classifying individual companies into allies and enemies. What the speaker failed to say is under which category does IFBA – which includes Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Nestle, and McDonald’s – belong. That would have been helpful in guiding how we in public health must engage with them – if at all.

Nonetheless, the presence of Big Food, Big Soda, and Big Alcohol (I suspect Big Tobacco was absent, or perhaps at least present discreetly) allowed NCD prevention advocates to tackle the ‘commercial determinants of health’ – global health academia’s newest buzzword – head on. From the audience, NCDFREE’s Rhea Saksena likened the ongoing interactions with industry to a ‘very tense couple’s counseling session,’ challenging companies to behave in a trustworthy manner if they want to be a ‘partner.’ Meanwhile, Paula Johns from Brazil remarked that “the best public-private partnership is taxation.” During the conference, there was general support for ‘sin taxes’ (which I suggest should be renamed ‘corporate sin tax’ to be precise), which Tim Evans described as a ‘triple win’; it does not only reduce consumption of unhealthy products and raise revenues for health – it also has an equity-enhancing effect.

Global health’s Desaparecidos

Like in any party, attending guests can’t help but look around and identify who were not invited. During the gala dinner, Suwit Wibulpolprasert, one of Thailand’s foremost public health leaders, started doing a roll call of Thai’s Fathers – the Father of Thai Universal Health Coverage, Father of Tobacco Control, etc. My seatmate whispered to me: “So many fathers – but where are the mothers?”

Meanwhile, my friend and colleague Mariam Parwaiz from New Zealand expressed her appreciation in the Twitter-verse: “Over 800 participants from 80 counties at #PMAC2019. One of the things that I really like about PMAC is that it’s a major #GlobalHealth conference that’s in the Global South. The future is Asia!” – to which I rapidly replied: “None of the keynote speakers though is from the #GlobalSouth #PMAC2019 #DecolonizeGlobalHealth.” Of course, I was not counting the Princess of Thailand who welcomed us all to the Kingdom.

Surely, concerns about lack of diversity and inclusion along the lines of gender, race, and nationality are not new but certainly need to be re-echoed. Johanna Ralston of the World Obesity Federation replied on Twitter that there was also an “absence of affected people as speakers other than a couple of side events #plwncd.” And while difficult questions were asked during sessions, another group hugely absent were the dissidents. A colleague told me that Thailand’s activist groups are generally not invited to PMAC each year. Thankfully, we have the People’s Health Movement – which another colleague described as PMAC’s ‘token opposition’ – boldly yet expectedly raising the difficult issues no one else will dare say in sanitized and well-scripted global health discussions. (Full disclosure: I’m a PHM supporter!)

Finally, there’s the big portion of our not-so-big global health family who generally did not see an invitation in their email inbox. My fellow Filipino colleague Gianna Gayle Amul, an emerging scholar from the National University of Singapore who is examining alcohol industry interference in Asia, tweeted her disappointment: “I thought I can just register and still come but apparently you can only do that if you actually have an official invitation… a little bit more exclusive #PMAC2019.” (By the way, Singapore is only two hours away from Bangkok! It should not have been difficult for her to come.)

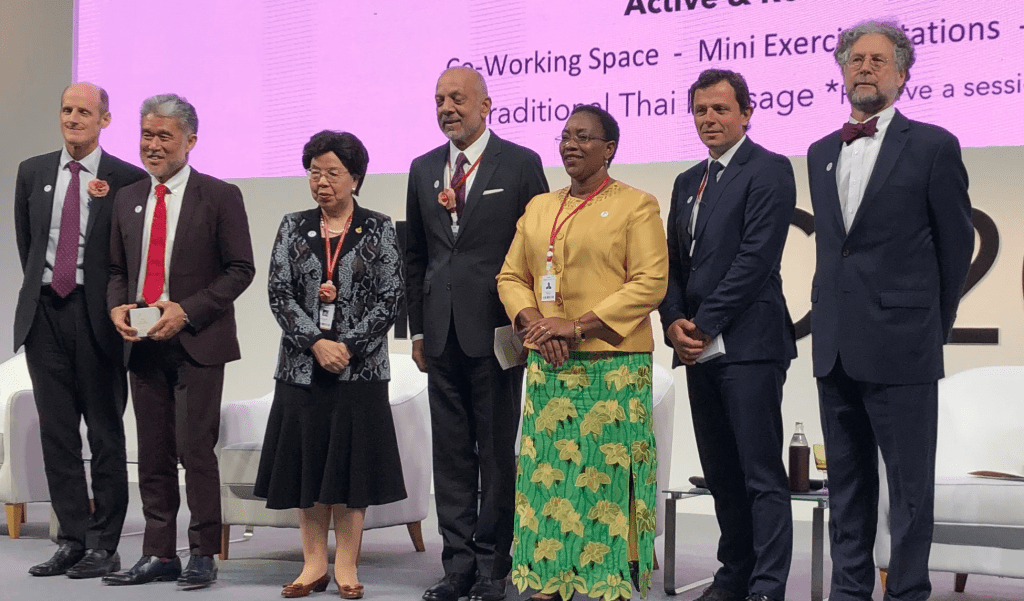

The return of Margaret Chan

PMAC 2019 also appeared to be a homecoming party for Margaret Chan, former WHO Director-General – or as Suwit repetitively

During the gala dinner, Dr. Chan and Suwit unleashed their hidden talent by pulling off a stand-up comedy stunt, where they jested about whether she is still earning a salary from WHO or not (she said no), being ‘raised’ by her husband post-WHO, and how some physical distance is beneficial to marital relationships. She publicly admitted that her only failure as DG – or perhaps the only failure that she can admit in public – is not having been able to convince member states to pass a resolution on LGBT health. But when Suwit, PMAC’s mastermind, asked her on what the major driving force in global health in the next decade will be, Dr. Chan flatteringly remarked: “PMAC, PMAC, PMAC!” Then the two waltzed to the tune of Carpenters’ “Close to You.”

While she received deferential applause accorded to a former DG, her statements about engagement with industry drew mixed reviews. During the opening panel, Dr. Chan repeatedly emphasized that her stand on NCDs is clear – however, it felt more confusing than clear as she urged tackling the corporate drivers of NCDs on one hand and helping make the industry “good guys” while keeping their profit on the other. She also said she did not want to comment on Tedros’ plan to engage with the alcohol industry since “he is in-charge now.” Harvard professor Jesse Bump then reacted on Twitter: “Shameful performance: Margaret Chan sings and dances to avoid a question about whether @WHO should accept money from the alcohol industry at #PMAC2019, focused on #NCDs.”

Leadership beyond imagination

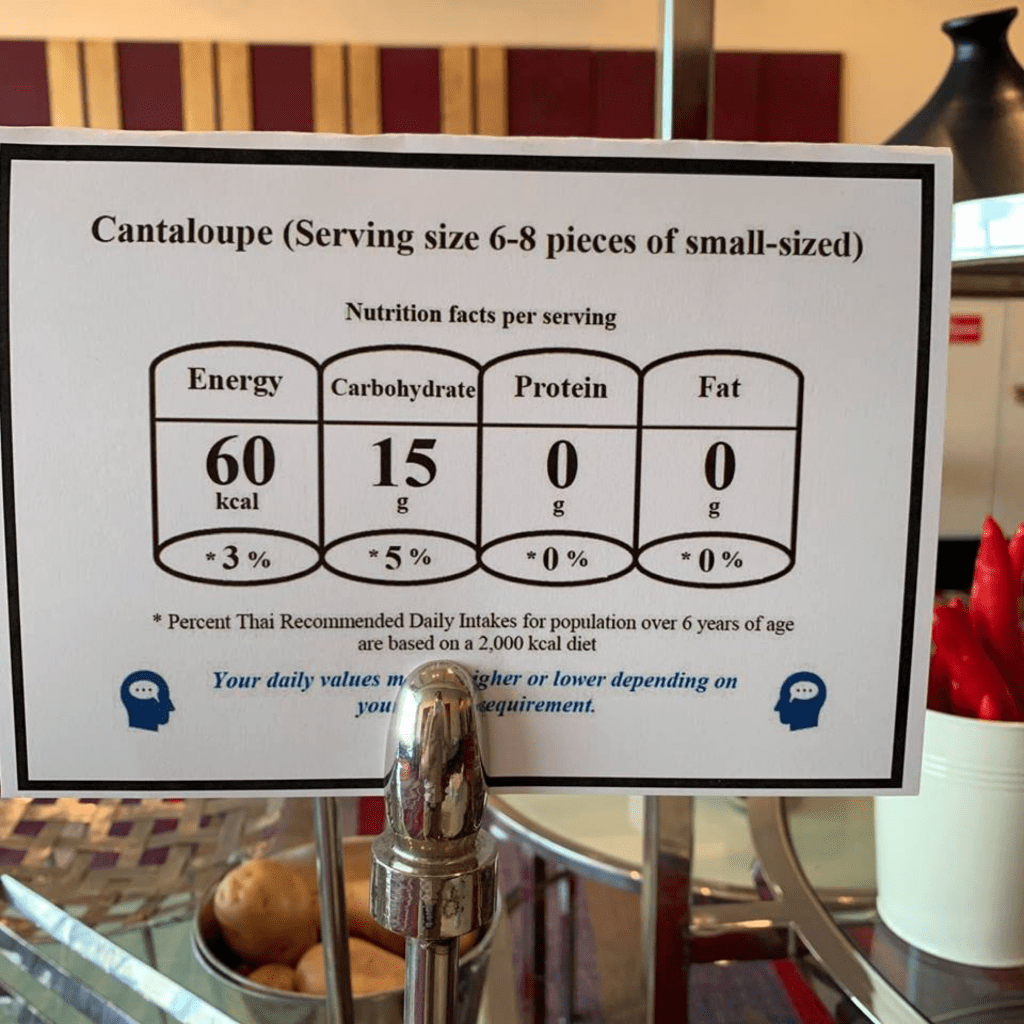

Given this year’s theme, PMAC was pressured to “walk the talk” by adding “Baby Shark” and other dance exercises at the start of sessions and installing food labels in buffet tables (though with lots of food wasted). This just shows that technical fixes in global health are quick and easy decorations. However, the real battle is how to get things done in a world where economic forces sell junk and the politics of change is controlled by a powerful few. This is what political economy is all about.

So what do we need to tackle the messy political economy of NCDs, of platforms such as PMAC, and of global health at large? I propose that it is strong, visionary, uncompromising leadership. Fellow Filipino Susan Mercado, former NCD head of WHO in the Western Pacific, eloquently articulated this during the plenary: “Leaders don’t work in the space that is easy. They work in the space that is beyond imagination.” I could say there were a few of them at PMAC 2019, but their tribe must increase.

May PMAC evolve into a space for courageous leadership and endless imagination. Kudos to the hardworking PMAC organizers – please don’t forget my invite next year! 😛