Yearly, since 1969, Nigeria suffers fatal Lassa Fever outbreaks. In a bid to increase awareness and curb the menace, the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) hosted a two-day international conference on the disease. Participants at the event got some encouraging vaccine news among others.

Tanko Al-Makura is governor of Nasarawa State, in northern Nigeria and lives each day with a scar inflicted on his “life and psyche” by Lassa fever. This is what he knows of the disease that has constantly killed Nigerians every year since 1969.

A male child among seven sisters, Al-Makura took to hawking cassava flour as a vocation because “that’s what I saw my sisters doing,” he recalls, standing in front of an audience of Lassa fever researchers and experts at the Abuja event held on January 16 and 17, 2019. “It inculcated in me a feminine and domestic instinct of care and nurture.”

It is the contact that puts many families in danger of contracting Lassa Fever every year.

Al-Makura was a 37-year-old father when his sons were diagnosed with a fever. One son was clenching. That “feminine instinct as a father” took hold and Al-Makura wanted to ensure his son didn’t cut his tongue between clenched teeth. “I got bitten on one finger. It was a small cut, no blood,” he says. “I didn’t know that was the beginning.”

The son died, the other one survived but developed profound deafness. Five days later, Al-Makura developed classic symptoms—fever, headache, stomach pain, tight chest, erratic breathing. The treatment by trial and error went on for two weeks. “There was no improvement, despite the fact that I was in a teaching hospital,” he says. “Linking my symptoms to Lassa Fever was my saving grace.”

Oyewole Tomori, a virologist who’s worked on Lassa Fever since it was first identified in 1969, made the diagnosis and insisted Al-Makura be sent off to a facility equipped to deal with a haemorrhagic fever like Lassa. The only hospital suitable in 1990 was in Lagos. A blood sample was sent to the US Centre for Disease Control in Atlanta, 9728 km away.

Fifty years on, the infrastructure for dealing with a yearly epidemic has changed; there is more knowledge about Lassa Fever; hundreds of articles on knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of Lassa fever have been published; the science is better understood. Yet the disease’s outbreaks continue to strike annually, claiming lives.

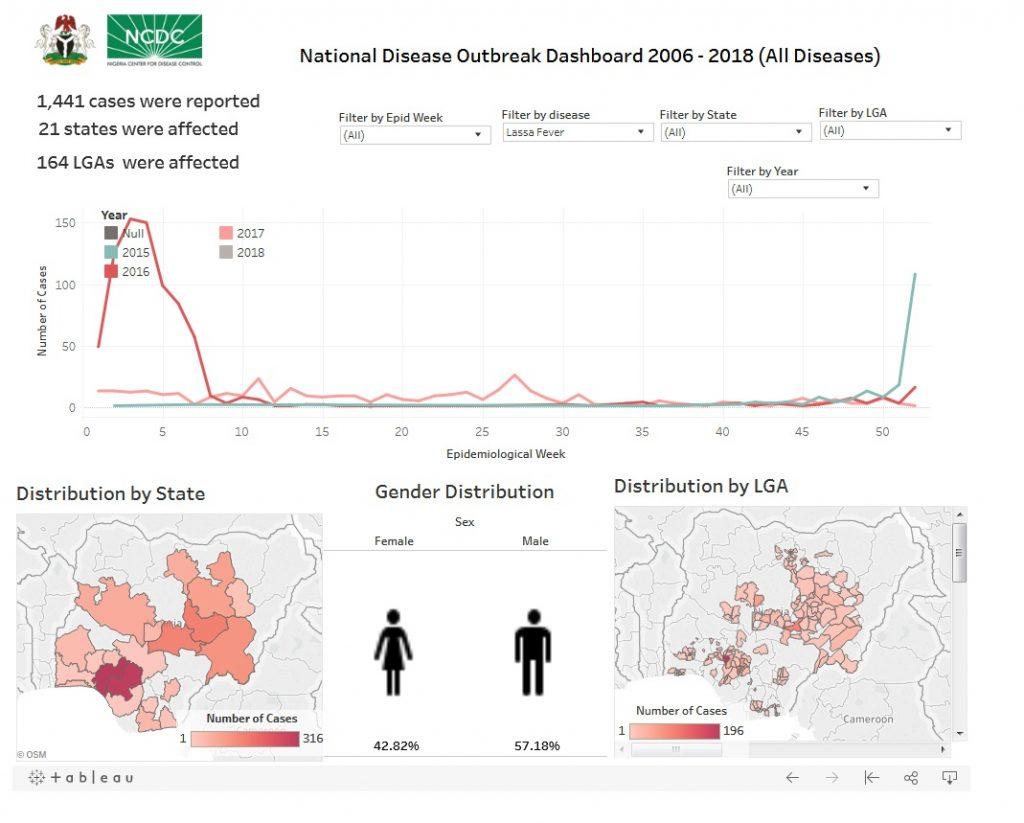

From 1969 to 1978, the outbreak was confined to four states in Nigeria. Nearly every state in the country has seen an outbreak in the last 50 years, and with it, a rising number of deaths. Between 2009 and 2018, only Zamfara has not reported a case.

The Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) has already declared an outbreak this year after 60 people across eight states were confirmed infected with the Lassa Fever virus in the first two weeks of January alone.

Despite the tons of knowledge-attitude-and-perception articles [nearly 160 papers were presented at the conference] published on Lassa Fever, the basic route of infection continues to make the country vulnerable. Environmental hygiene, personal hygiene, handling food materials, handling sick loved ones, handling patients—it is all in the mix.

In the lead up to declaring an outbreak, NCDC warned: “Lassa fever is an acute viral haemorrhagic illness, transmitted to humans through contact with food or household items contaminated by infected rodents. Person-to-person transmission can also occur, particularly in a hospital environment in the absence of adequate infection control measures. Health care workers in health facilities are particularly at risk of contracting the disease, especially where infection prevention and control procedures are not strictly adhered to.” It advised the Nigerian public to “focus on prevention by practicing good personal hygiene and proper environmental sanitation. “Effective measures include storing grain and other foodstuffs in rodent-proof containers, disposing of garbage far from the home, maintaining clean households, and other measures to discourage rodents from entering homes. Hand washing should be practiced frequently. The public is also advised to avoid bush burning,” it added.

Al-Makura didn’t know any other way to handle his ailing son years ago. He and his doctors were at risk.

“I was later informed that my infection was the result of the bite from my son,” he recalls. The outcome of Al-Makura’s bout with Lassa Fever is profound deafness. He’s been using cochlear implants since 2000 to process sound, “although with some distortion,” he says. “Every day, I have to wear a hearing aid for 18 hours.”

Every year, this message goes out: “Health care workers are again reminded that Lassa fever presents initially like any other disease-causing febrile illness such as malaria; and are advised to practice standard precautions at all times, and to maintain a high index of suspicion. Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDT) must be applied to all suspected cases of malaria. When the RDT is negative, other causes of febrile illness including Lassa Fever should be considered. Accurate diagnosis and prompt treatment increase the chances of survival.”

A lot needs to shift in manner toward Lassa fever.

“You are killing your loved ones, your doctor is killing you and the doctor is committing suicide from utter disregard for infection prevention and control,” says Tomori.

“My country is a country waiting for the lion to finish yawning before deciding to run,” he said. “Once it is down yawning, its ready to pounce on you.”

Infograph Credit: National Centre for Disease Control (Nigeria).