As India tries to navigate the transition from Lockdown 4.0 to Unlock 1.0 (quite oblivious of the totalitarian nature of the words we chose to represent our national response to the pandemic), it is worth reflecting upon our lost opportunity as a nation to address social equity and its direct corollary – mental healthcare.

But let’s start with two short narratives.

Narrative 1

Mr. S, a 65 year old married man, with high school education, a supervisor in a state run agricultural industry, from south India, developed paranoid schizophrenia in January 2020. Worry and uncertainty over his health and employment during the pandemic were added stressors, especially as he was the sole earning member of the family. He continued to work despite this, until he was placed on unpaid leave by his industry during the lockdown. The resulting isolation and increased contact with a spouse he had never really gotten along with made things worse and he decided to seek help in March 2020, by which time elective out-patient state run services had closed. With limited digital literacy, he could not access tele-psychiatry services. He was similarly unable to avail private healthcare because he could not afford costs. He remained in distress and attempted suicide in May 2020, which was fortunately averted. Subsidised central government run out-patient services resumed in June at which point he sought care immediately in Bangalore, was placed on medicines and social casework. He was offered in-patient care in view of suicidality but chose not to as his industry re-opened and he needed to return to work to support his family. Despite these challenges, Mr. S is recovering now but worries about the stability of his income due to the economic slowdown.

Narrative 2

Mr. A, a 67 year old married man, a retired English Professor, from North-Eastern India, was diagnosed with mild dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease in February 2020. He had come down to Bangalore for a consultation while visiting family. His family, recognizing his vulnerability to the pandemic, relocated to his hometown soon after, where he underwent physical distancing and shelter-in-place directives in relative safety and comfort. His pension and social security benefits, along with support from his wife and children, who were employed and worked from home, helped the family tide over this period. The family, digitally literate, was able to video-conference with their psychiatrist from Bangalore during this period. He received prescriptions through email, and medicines were home-delivered to his residence. Though unable to meet friends and relatives, he was able to stay in contact with them over the phone, which cheered him up considerably. Cognitive retraining and family interventions to address dementia continued over tele-psychiatry during this period. Restrictions on his movement led to a transient worsening of irritability but the family were able to seek consultation immediately and used guided art and music therapy to engage him. Mr. A considers the pandemic as a necessary evil but is looking forward to meeting people again.

Some insights and reflections

These are two very different experiences of mental healthcare during the pandemic in older adults – highlighted by social inequity. Mr. A, despite having the graver diagnosis (at that age) and living further away from the hospital, was buffered by the educational, financial, digital, family, social, community and environmental support that Mr. S lacked. Mr. S, despite living practically next door to the hospital, took 5 months longer to get there than Mr. A, on the other end of country. Both older adults have navigated the lockdown relatively well, and are fortunate in having been able to reach the psychiatrist at all – unlike many who could not. Psychiatric consultations in India have dropped between 20 and 50% across the country, so for every Mr. A and Mr. S who made it to us, there are 1-2 people who did not.

COVID-19 has been called the great leveller or equalizer, affecting the privileged and under-privileged equally. The truth is anything but that. The pandemic and the curbs placed upon the population, have exacerbated social inequity and placed fresh barriers in the pathway to mental healthcare. Further, social inequity is in itself a risk to mental health, and named as a contributory factor in 61-79% of mental health research. Lower and middle income countries (LMICs) like India (where 10% of the population hold 77.4% of national wealth), with a lead time of only three hours into the COVID-19 lockdown and an unprecedented migrant crisis, are seeing a heightening of social inequity.

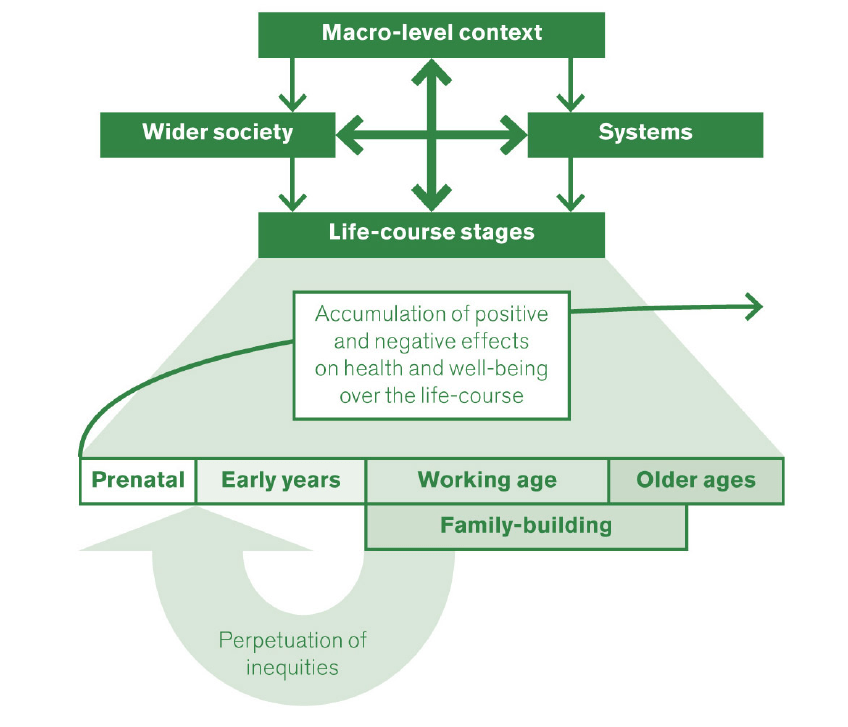

The social determinants of mental health are critical in formative years and continue to impact mental health and well-being (see Figure below), years to decades after the exposure to risk (social inequity). LMICs such as India suffer doubly – first from social inequity and income scarcity and second from the absence of robust plans, programmes and policies to address the impact of this inequity on mental health.

The way forward

Could this have been mitigated? Can these inequities still be addressed?

By providing food security, social security and uninterrupted access to non-COVID-19 health care during the lockdown, the government of India could have provided a social welfare buffer to help under-privileged groups tide over this lean period.

The district mental health programme (DMHP) can be utilized to provide mental healthcare in the community and at the primary care level to provide services while ensuring minimum population transit. India can learn from Europe and ensure comprehensive coverage of home delivery of medicines with the service of community pharmacists so that people do not run out of their medicines while sheltering in place. Free drug counters in government hospitals should reopen at the earliest possible opportunity. Digitisation of mental health services should use intermediaries to assist penetration in a country where digital illiteracy is estimated to be at 90%. Provision of food security and social welfare to marginalized communities including the informal labour sector could have averted and can still help address the migrant crisis.

There is potential for mental healthcare to be provided in the community and through primary healthcare that can be tapped. Mental health cannot be achieved without an investment in social welfare.

Footnote: A few definitions

1. The WHO defines mental health as a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community.

2. They define the social determinants of mental health as the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life. These forces and systems include economic policies and systems, development agendas, social norms, social policies and political systems.

3. They define healthy ageing as the process of developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables wellbeing in older age. Functional ability is about having the capabilities that enable all people to be and do what they have reason to value. All of these have been compromised during the pandemic.