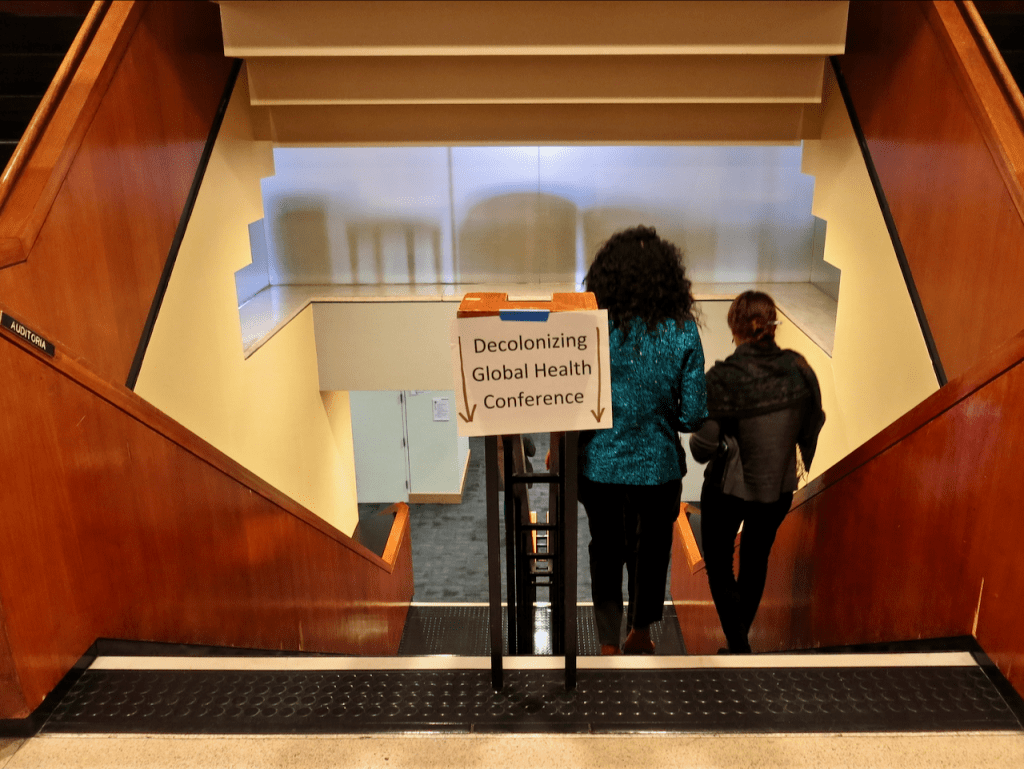

Not every day we attend conferences that in their announcement declare global health to be “only the newest iteration of what was formerly international health, tropical medicine and colonial medicine”. Which is precisely what attracted this grey-haired whitey – working in what is still called an Institute of Tropical Medicine – to the “Decolonizing Global Health” conference organised by a student committee in the Harvard School of Public Health. Apart from the decolonization theme itself, of course. After all, I’m Belgian.

Unlike ITM at the river Scheldt where the Congo boats moored, Harvard is situated on the banks of Charles River, Boston. And while Boston never had a formal colony, it is the capital of a New England settler state, and its United Fruit Company plantation hospitals were field stations for Harvard students till deep into the 20th century. Which made the opening remarks of Elizabeth Solomon – one of 80 survivors of the Massachusett Ponkapoag tribe – rather fitting: “Here is where we interacted with the visitors. Here is where those who survived remained (…) But colonization is not limited to centuries ago. The systems of colonization continue, in this place and others (…) Each and every one in this room is a colonist. So please be mindful, introspect, and respect”.

Solomon’s plea did not fall on stony ground. Among others, Anne-Emmanuelle Birn made it clear to everyone in the conference hall that a straight line goes from erstwhile ‘tropical medicine’ – “actually reinforcing the political and social stratification between colonizer and colonized” – to present-day ‘global health’ dominated by “Tata kills, Tata funds” and Davos-style philanthrocapitalism. Yesterday’s colonialism and today’s coloniality have one thing in common – the reinforcement of inequity – and the current mainstream global health is essentially colonial, hence needs to be decolonized. One possible and much needed way of doing so is to decolonize global (and international, and tropical) health syllabi. Which is one of the more immediate aims of the student committee that came up with the great idea to organize this conference. But it is not enough: Harvard scholar Melissa Barber outlined a chain of academic mechanisms maintaining the global health community as it is, and which all need to be redressed – “(1) Gatekeeping for people entering; (2) Selecting of global health frameworks; and (3) Legitimizing mainstream global health initiatives”. Much remains to be done before we arrive at “a vision of global health that is equitable, reflexive, and anti-colonial in both delivery and discourse”.

In the closing plenary, distinguished health and equity champion Mary Travis Bassett pointed out the essence of the way forward for genuine decolonization: “replace the happy handholding of global health partnerships with solidarity, meaning equal value and rights of all humans”. She concluded by asking all of us to “apply the principles of solidarity on the whole globe, not only far away, but also in your own environment”. Which brings me back home, in my own academic environment, at ITM. There is little doubt that our own house needs decolonization too. Are we willing to take on the task?