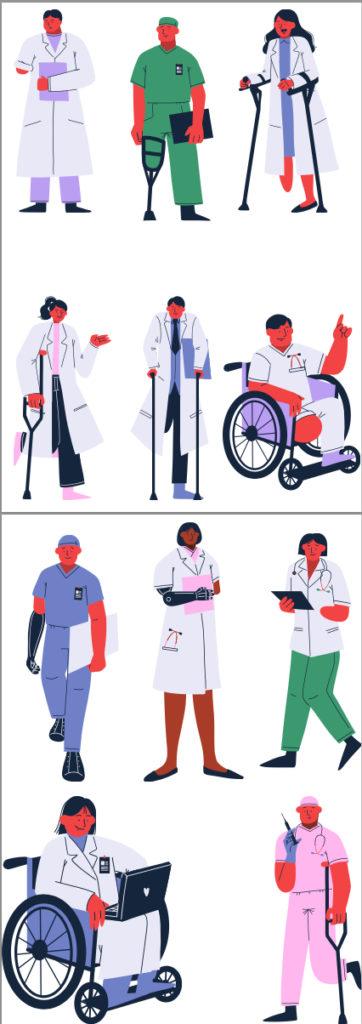

Globally, medical students and doctors with disabilities have been denied their rightful inclusion. This also rings true for India, where almost 80,000 doctors graduate each year.

It is estimated that so far 0.38% of 1614777 medical and dental aspirants registered as having a disability. Only 43% of these cleared the qualifying nationwide entrance examination (National Eligibility cum Entrance Test). This is the first step towards eligibility which is followed by assessments of ‘compatibility for medical training with a disability’. True, these numbers have been slowly and steadily increasing since 2016, when data has been made available for the first time. However, their inclusion through training and practice remains extremely fraught, blocked by irrational yet dominating ableist narratives. Data on those in training or practice remains unavailable.

Paradoxically, barriers to inclusion and challenges to full and effective participation have become commonplace while attempting compliance with inclusion standards introduced under the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act of 2016. Compliance with the letter appears to be the objective of recent inclusion efforts, at times jeopardizing harmonization with the spirit of the law or even the United Nations Convention on Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD). Eligibility norms/standards stipulated for entry into training assess aspirants on the basis of impaired body parts (such as one arm or one leg affected). This arbitrary classification of the experiences of persons with disabilities, itself dehumanizing, is then used to exclude or constrict training opportunities. Similarly, these norms find their way into how authorities determine suitability of qualified doctors with disabilities for practice within government-run health establishments. Meanwhile, no details on curricular and assessment accommodations, accessibility and inclusion standards or disability support services have been made available. Apart from the lack of guidelines, pervasive underlying biases, prejudicial attitudes and misconceptions about disability may be hampering education and employment opportunities for the disabled in the field of medicine.

Doctors with disabilities can offer valuable insights for patient care from their lived experiences and this may prove extremely beneficial for both health systems and patients. Against this backdrop, the International Day for Persons with Disabilities (IDPWD) 2021 theme, ‘Leadership and participation of persons with disabilities toward an inclusive, accessible, and sustainable post-COVID-19 world’, is a clarion call to advocate for inclusion, including for doctors with disabilities. The eighth SDG goal is to “Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all”. It commits to full and productive employment of persons with disabilities, just like Article 27 of the UNCRPD recognizes the right to work on an equal basis with others.Those registering for disability support most frequently report learning disability. In India, such persons are barred entirely from medical training. Systemic reforms and educator-led investments have the greatest significance when promoting a neurodiverse workforce. In other words, the onus is on healthcare systems to change.

Some changes to the healthcare system to fight for in the post-COVID era:

The opportunity to be truly transformative, going beyond the letter and even spirit of laws and building a diverse and robust healthcare system, is now.

Thanks for the information, I am a NEET student at DR Academy they provide best guidance for NEET aspirants.