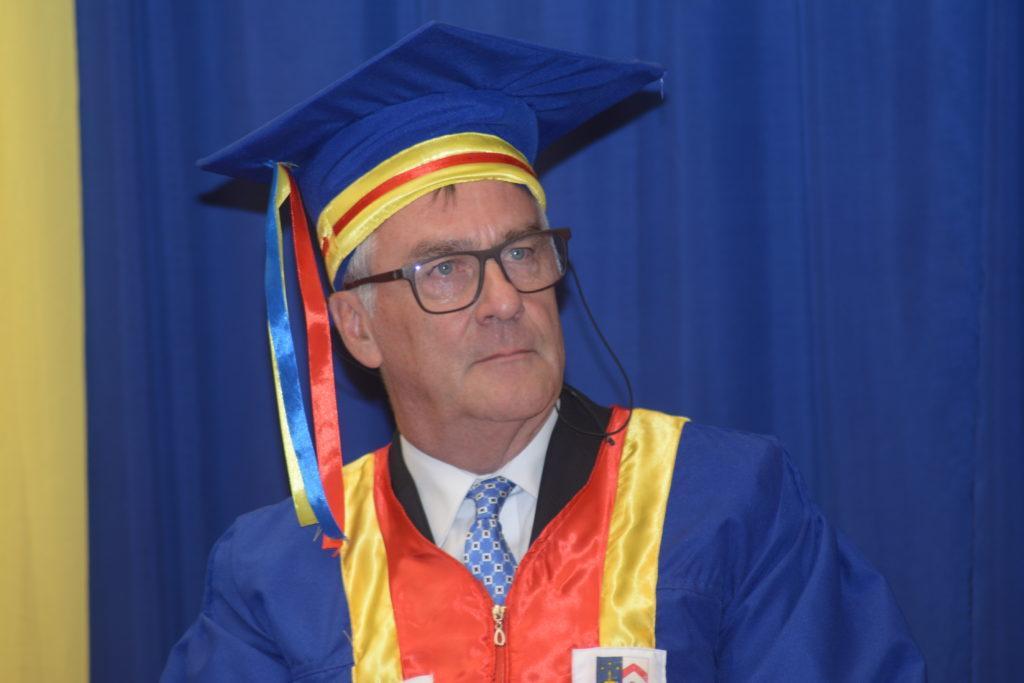

I turned 65 in July, and have shifted since August 1st to the status of (young) retiree. That is indeed the rule at the Institute of Tropical Medicine (ITM) in Antwerp, and for that matter also at Belgian universities. Not that I would have considered to stay longer (even if it were possible). I was/am actually looking forward to more time for other things in life… and it is thus without regret that I leave the busy professional life of a professor at the public health department behind me. It will however still take a bit of time to find and strike the right balance between further interest in “public health” (even if mostly passive from now on), and space and time for new things. But let there be no misunderstanding: I enjoyed very much the three decades of work at ITM. I consider it a privilege and an honor to have been able to work at this prestigious institute, with the opportunity to meet and collaborate with outstanding people – in Antwerp, as well as overseas! And so I happily accepted Kristof Decoster’s invitation to write an editorial for IHP on the occasion. Having no intention whatsoever to engage in a self-centered apology, I hope this piece can be of interest to the reader who may perhaps recognize a number of things and find in it inspiration for further thought.

What has been my path over the last 40 years (of which 30 at ITM) and what do I take from this journey that could be of relevance for others, and perhaps especially for younger faculty at the public health department of ITM?

I studied medicine at the Catholic University of Leuven and graduated in 1981. I am the product of a traditional medical training curriculum, largely geared towards the provision of individual curative medicine, in line with the dominant biomedical perspective. Most of my teachers were brilliant clinical specialists, many of them operating at the top of the health care pyramid in Belgium: i.e. a tertiary hospital-based environment with high-tech diagnostic support services (NB: in the 70’s and 80’s, the formal training of general practitioners/family doctors by general practitioners/family doctors was still in its infancy).

In my last year of medical school in Leuven, I attended the postgraduate course in Tropical Medicine at ITM. Looking back, I believe I was driven by a blend of curiosity, the longing for “adventurous” work in the world at large, complemented by a mix of idealism and probably also a certain amount of naivety. The fact that I was born in Burundi and lived with my parents and siblings for a couple of years in Ethiopia in the early 70’s, no doubt also contributed to the choice to go and work in Africa. Africa is indeed an important part of my (layered) identity.

This 5-month course at ITM was a major eye-opener. I discovered (in addition, of course, to the exciting confrontation with tropical diseases) an entirely novel perspective on health, health care and health systems – and a language to reflect on it! The late Professor Harry Van Balen, then professor of public health, was key in that discovery. What was so new then, for a 25-year young Belgian medical doctor freshly trained at one of the top Belgian universities? Well, in the first place I discovered the notion of “health systems”, even if at the time I did not yet fully grasp its public health relevance. Like for so many other concepts and theories, I gradually developed a deeper understanding of systems thinking over the years when studying health systems in a variety of contexts, in South and North, and over prolonged periods of time. Field exposure is indeed fertile ground for interaction between practice and theory. I also increasingly realized that health systems are social and political constructs, shaped by values and choices, in the past and present. My horizon further widened with the encounter of a “non-medical” view on health, going beyond the mere absence of disease, and integrating the notion of social determinants in health. I began to grasp the need to broaden health care beyond the provision of individual curative medicine, with due attention for the often undervalued and poorly funded preventive and promotional care, at both populational and individual levels. Professor Van Balen emphasized the need to prioritize health activities on the basis of evidence, available resources, but also in line with people’s perspectives and priorities. In short, it was at ITM that – for the first time ever – I heard about Primary Health Care (PHC) and the famous 1978 Alma-Ata declaration!

Later, when I worked for the Belgian Technical Cooperation in the former Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) (from 1983 to 1990), all this increasingly made sense. The long-term “confrontation” with, or rather immersion in the reality of (local) health systems in Zaire eventually proved to be a powerful opportunity to enhance my understanding of the “what”, “how” and “why” questions related to the planning, organization, management and evaluation of health systems. With some hindsight, I like to see my stay in rural Zaire (in the Kasongo and Bwamanda districts respectively) as a “learning site” avant la lettre. This learning process was further structured and consolidated in the one-year Master’s programme Community Health in Developing Countries at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (which I followed in 1988-89).

End of 1990, I joined the public health department at ITM. My work at ITM was characterized by a mix of research, teaching and service delivery/capacity building activities in the broad field of health systems and health policies. I was given the opportunity, liberty and autonomy to study health systems at all levels and in all their dimensions, in a range of countries (Belgium, Benin, Guinea, India, Mauritania, Uganda, Zimbabwe…), and over longer periods of time. This experience strengthened my understanding of public health concepts and has been a continuous source of inspiration for both my teaching and research.

I cannot end this brief account of my stay at ITM without explicitly applauding the decolonization debate that is today also sparkling within the walls of the institute, largely thanks to a younger generation of faculty, from North and South. It is a most fortunate development. Indeed, I am convinced there is a need to think thoroughly through the complex issue of decolonization and reflect on how this (necessary) process can eventually have a positive impact on the interpretation and framing of the rich cultural patrimony of ITM, the design and running of our educational programs, the set-up and operation of our international research platforms, the nature of our interaction with our Southern partners, and, last but not least, the composition and functioning of our institutional governance structures.

Now, what is in this story for younger colleagues? It would be presumptuous to talk about “lessons”. Times have changed, each one of us is different, and my experience is by no means unique nor a “blissful one” for everybody. Perhaps an elegant way out is to formulate a number of broad suggestions…?

Let me share three of them.

First, as much as possible (as permitted by the institutional leadership), do take time for prolonged exposure to “the field” of health systems and disease control programmes, combining depth with breadth. Try to get this experience in a variety of settings, and not only in exceptional conditions (like in the case of a pandemic for instance), but also under routine day-to-day circumstances. A key element of that exposure is time: to observe what is taking place, to listen to people, to take stock of their priorities, and to take this all into account when critically reflecting on one’s own work. Could this be the public health version of “slow science”, perhaps?

Second, go for a personalized and optimal balance between research, teaching and service delivery/institutional capacity building activities in your academic public health work. This mix has great potential for creating synergies and boosting cross-fertilization. But people are of course not interchangeable. No one should do exactly the same as others. Being part of a multi-purpose (and multidisciplinary) team is therefore important. Some team members are fond of teaching and excel in it, others are more attracted to research, and still others thrive when engaging into institutional capacity building of overseas partners. The team as a whole can then strike a sound balance between the three above-mentioned core academic activities. An important implication is that institutional performance assessment processes should also focus on how teams perform, and not only on individual faculty.

Third, build a clear vision on what exactly it is that you want to strive for. Indeed, if it is not clear where to go to, then the risk is that one goes in all sorts of directions … To quote Antoine De Saint-Exupéry: « on ne peut montrer le chemin à celui qui ne sait où aller ». What is the sort of health system we aim for? And why? Such a vision builds on a mix of organizational and managerial principles and a clear set of values as one’s guiding compass. In my case the philosophy and strategy of PHC has always been, and still is, a most valuable reference framework. PHC is still more than relevant today. Its concrete implementation will of course always need to be context-specific. Leave no room for “dogmatic” “copy and paste” models. As nicely put by the French anthropologist Jean-Pierre Olivier de Sardan in his recent book (La revanche des contexts. Des mésaventures de l’ingénierie sociale, en Afrique eu au-delà, Karthala), if the (specificity of) the context is not taken into account, there will be a backlash, for sure…

I wish you all the best in your future endeavors.

Warm regards,

Bart Criel (bcriel@itg.be)

Riche expérience cher Professeur,

Bonne retraite!