“The world is but a canvas to the imagination” Henry David Thoreau

Nothing provides humanity with such of an opportunity as that of a crisis. At the beginning of 2020, many of us working in the field of health policy and systems research continued about our daily tasks in a routine manner, following the expert prescriptions we hoped would heal the voids that exist within our health systems. Since January 2020, signs were mounting that a crisis was heading our way, and when the Covid-19 related Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) turned out a full-blown pandemic, we faced the reality that many of our ways of doing and being no longer sufficed. Our well-polished tools and approaches, many which we knew were insufficient but the best available at our disposal, left us ill-equipped, as the landscape we were applying them to changed overnight. Something more was and is needed.

Social innovation scholars like Frances Westley have been drawing upon fields such as ecology to understand the process of social change for several decades. Building upon the work of CS Hollings on resilience, social innovation scholars regard shocks and crises, not as problems to be solved but rather, as opportunities for self-reflection and as windows of opportunity for the emergence of new ideas and possibility. Global health crises, such as Covid-19, highlight how existing health system patterns and processes are failing to serve those in need most effectively, efficiently and humanely. However, this crisis could also be the catalyst for innovation leading to the creation of radically different and durable systems, free of past inequities and burdens.

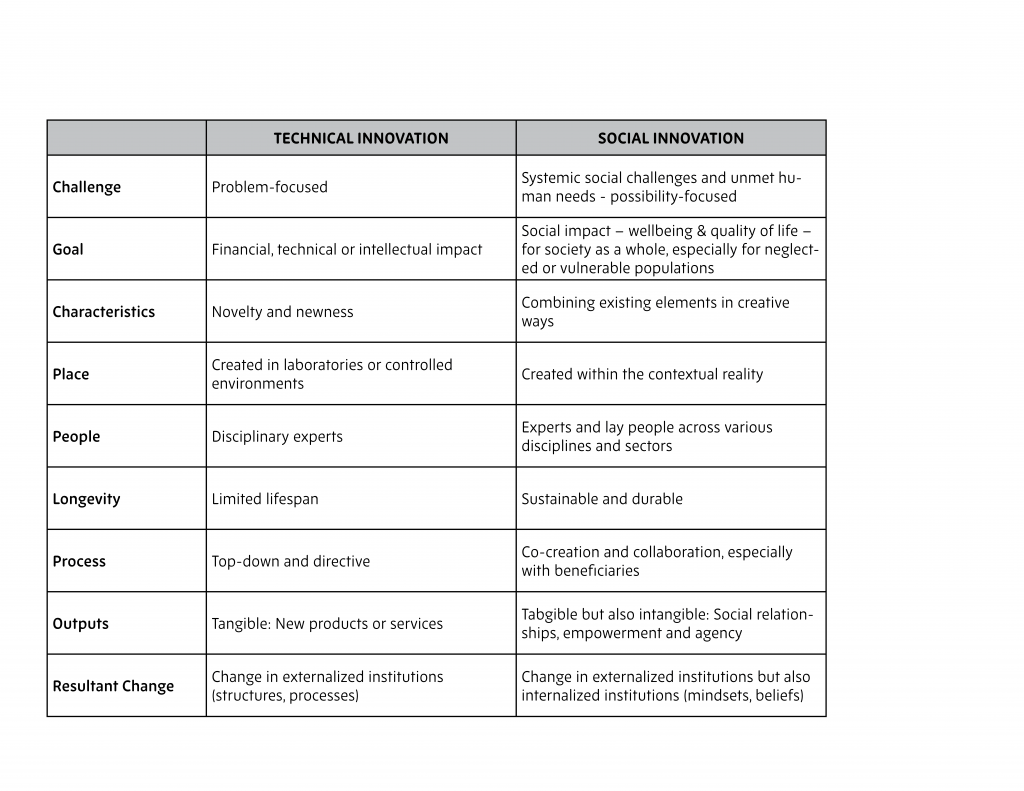

But what type of innovation might set us on the path to such transformation? Certainly, the need for technical innovation, in the form of rapid diagnostics, a vaccine and other therapies, in the Covid-19 pandemic cannot be discounted. But while we wait for such technical innovation to emerge, social innovation should also play a valuable role in health system response efforts. Table 1 provides characteristics that distinguish technical from social innovations. Key amongst the distinctions between the two approaches is how technical innovations have a problem-focused starting point while social innovations have a possibility-focused starting point. The significance of these distinct orientations is captured by Peter Block who notes: “problem solving can make things better but it cannot change the nature of things, especially systems which are complex and adaptive”.

Social innovation is not a new phenomenon in health. Throughout history, there have been examples of social reformers and innovators in health – individuals with great courage, who at a time of crises brought new hope through social innovation. Fast forward to 2020, we as part of the Social Innovation in Health Initiative, have identified and studied a large number of social innovations in health, implemented in low and middle-income countries right at the frontlines. These social innovations were triggered by the health system failures and institutional voids that are hindering millions of people from accessing equitable and quality health care.

A key feature of the social innovation initiatives we have been studying is that they do not address health system challenges through top-down imposed implementation, but rather emerge, often organically, from the embedded and lived contextual reality and through the community involvement. An example where we have seen his bottom-up nature of social innovation reflected so well is in the Kaundu Community-Based Health Insurance Initiative. The Kaundu Community Health Centre, serving a very low socio-economic population in a rural district in Malawi, has been able to extend service delivery to its local population, and reduce out of pocket health expenditure, through establishing a localized health insurance scheme that is fully embedded in the community and traditional leadership structures. The ‘how’ (the implementation) of social innovation is often where the greatest novelty can be found.

At the same time, however, social innovations rarely function in isolation of the government public health system. Our work showed over 80% had some level of engagement or partnership with their local Ministry of Health. A second social innovation from Malawi, for example, Chipatala Cha Pa Foni, illustrates how an idea that arose from a young Malawian citizen and was implemented as a partnership between VillageReach (a NGO), Airtel (a private company) and the Malawian Ministry of Health, can become a central component of the national Covid-19 response. Chipatala Cha Pa Foni is a national nurse-led health information call centre that provides health information free of charge to all citizens. By being embedded in the health system across all levels, social innovations have demonstrated a great degree of responsiveness in dealing with arising health issues, creatively adapting their models in response, serving as a bridge between community, the government and other sectors and by unlocking dormant resources.

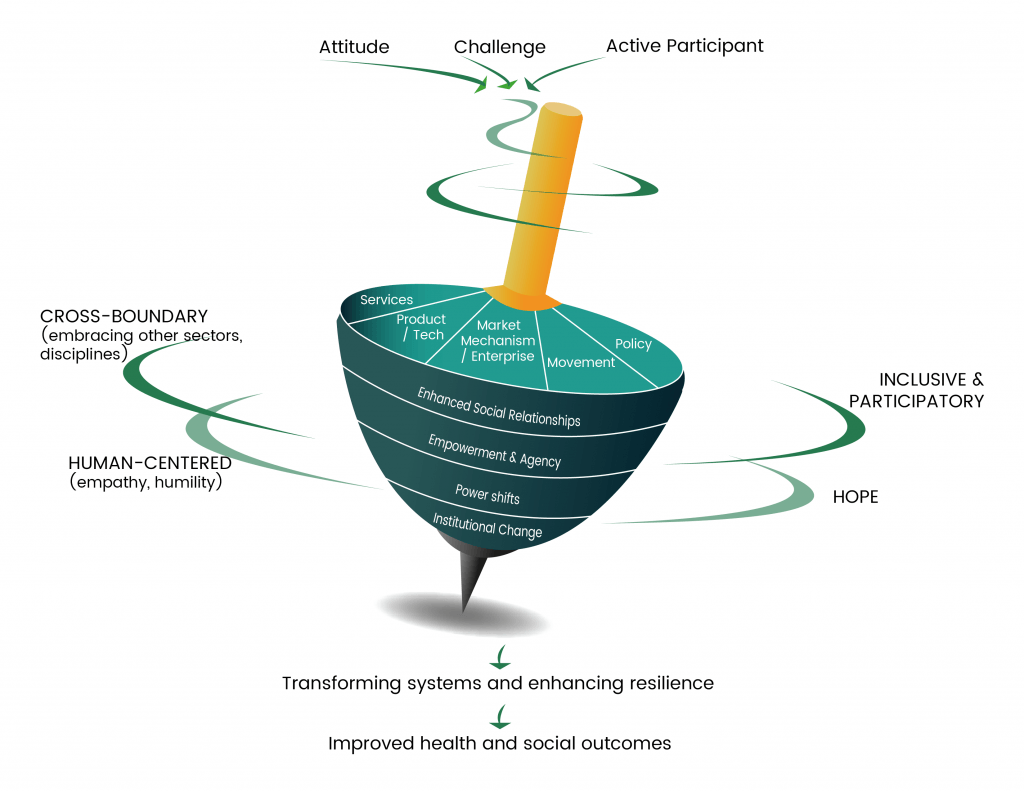

Beyond filling much needed service gaps, social innovations are significant for their role in promoting community capacity and shifting in institutions and power dynamics between various health system actors. In the current Covid-19 context, for example, learnings from new social innovations are emerging from many settings and showing how citizens are stepping into and building leadership within their own communities and households to find ways to curtail the virus. Community Action Networks established by residents in Cape Town, South Africa are such an example of a citizen-directed social innovation against Covid-19. Social innovation can support this bottom-up democratic action through its embodied values of inclusiveness and participation.

Health systems all over the globe, and even more so in low- and middle-income countries, are under pressure from this pandemic and it will yet again test the systems’ resilience. Based on our research conducted in social innovation the past 5-years, we see promise that social innovation could contribute to health systems in two ways. Firstly, by strengthening the micro-level health systems response to Covid-19 and in so doing relieve the pressure at the macro-level to steer and steward the response solely from the top. Engaging with social innovators at the frontlines or providing new non-traditional actors the opportunity to present creative solutions expands our options for addressing this local and global challenge. Secondly, the pandemic has created a new window of opportunity for social innovation at a systems (macro) level. By learning from resilient social innovations which were created, implemented and sustained by and with people right at the heart of health systems, we can move beyond the rhetoric of people-centredness to build practical strategies. Contextually and community-embedded social innovations can serve as a practical roadmap to guide decision makers how to transform health systems in the face of the storm.

Acknowledgments: The Social Innovation in Health Hubs at the University of Malawi, Makerere University, the University of the Philippines and CIDEIM (in partnership with ICESI University and Pan American Health Organization), the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases and the other partners of the Social Innovation in Health Initiative.

Welcome to the SHAPES article series, hosted by IHP. SHAPES is a thematic working group within Health Systems Global, which facilitates discussion, debate and collaboration around social science approaches for research and engagement in health policy & systems. In the months leading up to the 6th Global Symposium on Health Systems Research in Dubai (Nov 2020) SHAPES members will be blogging about the Symposium's theme of "re-imagining health systems for better health and social justice" through a social science lens.

View entire SHAPES series