“Hey, aren’t you afraid of dying from the coronavirus? No! I’m afraid of dying dismembered and be blamed for it”, a Chilean cartoonist tweeted a few days ago. And that is more than just a perception for hundreds of thousands of women across Latin America who flocked to the streets on Sunday, in commemoration of International Women’s Day (8 March).

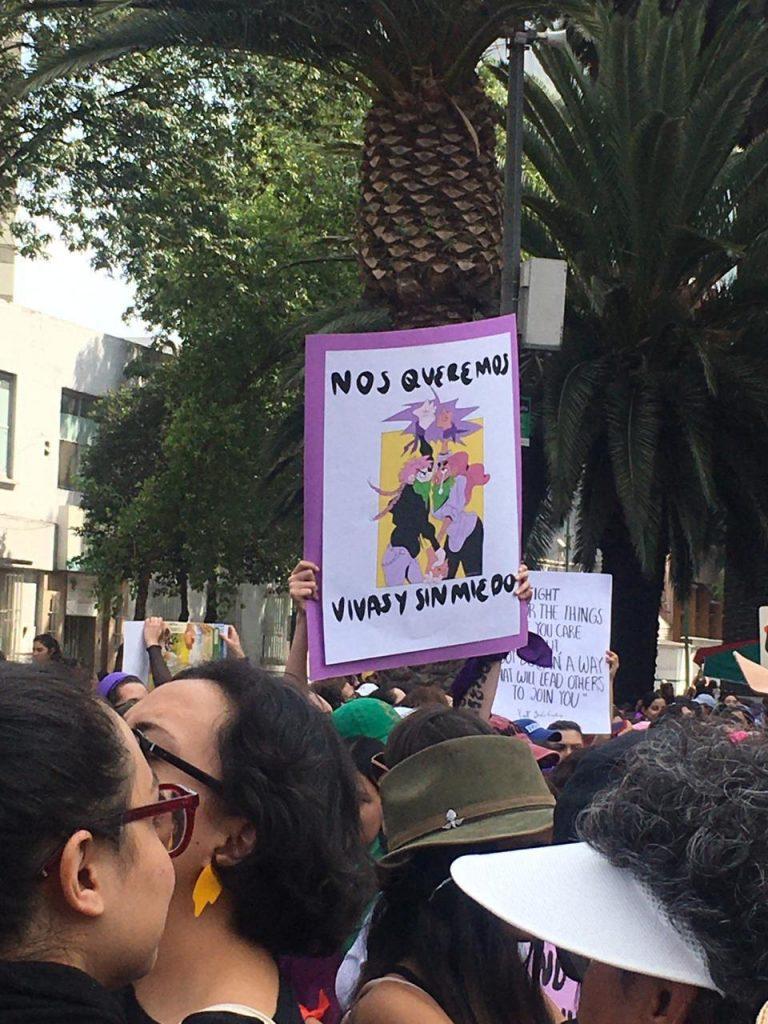

Living and working in one of the biggest cities in Latin America myself, I felt the urge to join the march against the femicide epidemic in my host country. Mexico, that is, where violence is rampant and 10 women are being killed every day according to estimates. ‘México lindo’, where women have had enough of the macho violence and keeping silent because of fear. Now, many of us are angry and have decided to claim the streets. Some even burn whatever crosses their path.

Mexico City’s authorities reported that approximately 80 thousand people participated last Sunday, despite the coronavirus confirmed cases (7 cases at the time of writing) and despite threats in social media claiming that there could be attacks against women participating in these demonstrations.

Additionally, on Monday March 9th, there was also an unprecedented national strike. People massively responded to the call ‘A day without women’, disrupting the usual routine of a hectic and crowded city: most banks were closed, metro stations and shopping centers were empty. The national strike was a call to demand for respect of women’s rights, a call to protest against gender-based violence, inequality and macho culture. Women were asked to miss work, school, abstain from buying and limit their social media activity. Even the private sector supported women who went on strike, despite the economic loss to the Mexican economy (around 1.370 million US dollars).

But why is there so much more anger now than ever before? I found a timeline that helps you understand why a broader spectrum of Mexican society is supporting the feminist movements now:

March 2019 #MeTooEscritoresMexicanos or “Me Too Mexican Writers”

Social media testimonies of sexual misconduct against writers, musicians, actors and journalists. These testimonies were discredited due to the anonymity of the victims.

August 2019 #NoMeCuidanMeViolan or “They do not take care of me, they rape me”

Police officers raped a teenage girl, igniting strikes in Mexico City. Protesting feminist groups spray-painted one of the city’s most iconic monuments, El Ángel de la Independencia.

November 2019

And the list goes on. On March 8th -March 9th, 21 women were killed.

Mexican president Andrés Manuel Lopez Obrador gave a shameful response to the increase in women’s violent deaths: “I don’t want femicides to overshadow the lottery”. He also suggested that last Monday’s strike was part of a plot against him by his political opponents, and claimed that neoliberalism was the reason there were so many femicides, as if gender-based violence was a by-product of neoliberalism alone and hadn’t existed before. In a similar vein, the governor of the state of Chiapas mocked women striking on Monday, saying they were cleaning their homes.

Official statistics estimate that there are 11 acts of sexual aggression against women for every act performed against men. Between 2015 and 2018 killings of women increased by 57% (from 2,383 violent deaths in 2015 rising to 3,752 victims in 2018), even though many states increased and reinforced sanctions in an attempt to curb femicides. Over a 4-year-period, 12,378 women were killed. In November 2019, the Mexican Minister of Security stated that 125,000 women had been victim of violence in the country that year alone. Only 1 out of 5 murders are investigated as possible femicide, that is, around 80% of the perpetrators won’t be sentenced the way they should (as there are harsher sentences for femicides than homicides).

With these figures and the testimonies of so many women who have died or had to endure violence due to societal gender roles, I don’t feel indignation for vandalized monuments and graffiti claiming justice and respect for my life and other women’s. I stand for myself, for the women who stood before us and for the next generations of girls and women that hopefully won’t have to protest in order to keep themselves alive.