Last week, I had the pleasure of participating in the 19th WPA World Congress of Psychiatry in Lisbon (21-24 August). In case you didn’t know, WPA stands for ‘World Psychiatric Association’. But as we all know (or should know), there is no health without mental health, and I was therefore proud to represent ITM at this Congress!

Back in September 2011, mental health was still – unfortunately – excluded from the political declaration of the UNGA High-Level meeting on NCDs. Since then, a lot has changed, however. Prof Norman Sartorius mentioned in his opening statements how challenging modern times are for psychiatry. New levels of stress affect younger generations, new ideas have popped up in society about (mental) health and intimacy and there is more and more emphasis (and pressure) on individual performance. In addition, age-old troubles (like conflict ) as well as new trends such as climate change also increase the burden of mental illness in our times.

These trends have not gone unnoticed, see for example the WHO’s mental health action plan for 2013-20, last year’s UN member states’ statement on NCDs (which included also mental health promotion), and the growing evidence for integration of mental health with the other NCDs. But one can still wonder whether this ‘supply-side’ effort really addresses the issues at stake. I do not think so, and I am not alone in this (happy to hear other voices!). Let’s first explore what is OK about the new ideas, and then look at what could be improved.

Since ‘stating the obvious’ is part of “excellent” science, the obvious observations confirmed at this conference included, among others: poverty is not a good thing, and even bad for your health; women living in adverse situations have more health problems than women living in more wealthy situations; and if you are depressed, you may have a bigger chance to develop diabetes (or any other illness related to not taking proper care of yourself).

When it comes to NCDs, then, interesting developments beyond the obvious behavior issues that link mental health to NCDs pointed to a growing body of knowledge on how genetic and environmental factors cause co-morbidity and worsen clinical outcomes of both mental and physical illness. And this knowledge is indeed increasingly applied, for example, in addressing comorbidity of diabetes with mental illness in the INDEPENDENT (“INtegrating DEPrEssioN and Diabetes treatment”) program in India.

There were some interesting reflections on psychiatry itself at the conference. Sartorius quoted no lesser names than Plato and Descartes to make his point. While Plato had famously declared, “The greatest mistake in the treatment of diseases is that there are physicians for the body and physicians for the soul, although the two cannot be separated“, Sartorius singled out Descartes as the one that separated body from mind through his notorious ‘substance dualism’, that states that the mental can exist outside of the body, and the body cannot think. ‘I think, therefore I am’ proves not very helpful for the now broadly accepted need to bridge the mind-body gap. For some examples of this blossoming new paradigm, see Pratima Singh talking (on YouTube) about the emerging science of the gut-brain connection, or the appreciation of the importance of the gut micro-biome in chronic conditions. At the conference, Richard Holt showed that endocrinologists also know their classics, quoting Thomas Willis, an early English physician and anatomist, who wrote during the mid-1600s that diabetes is caused by “sadness or long sorrow and other depressions.”

Insightful reflections on psychiatry also came from Vikram Patel, who complemented the ‘outside-in’ challenges (of the world to psychiatry), with the ‘inside-out’ challenges that come from within psychiatry itself.

Given that psychiatry is in essence different from other medical specializations (there is no clear mad/sane binary, the discipline actually aims to heal the divide between body and mind, has a difficult relationship to diagnoses and epidemiology, and should actually be recognized as the origin of ‘patient-centered care’ – dixit the same Vikram), it is time to realize how the ambiguous classifications in the DSM V and ICD 11 have actually caused a lot of mental health research to focus more on statistics and diagnostics than on persons. This is the ‘credibility gap’ of psychiatry that needs to be addressed. Urgently.

Most important here is to respond to real problems of real people. Effective and credible mental health needs to put the patient – or rather person, or even better the family – central. As you probably know, 1 in 4 people have a mental health problem and impressive statistics are thrown around to get the attention of policy makers and donors. But many normal (sic) people do not recognize what mental health specialists call ‘disorders’ as problems that require special treatment. As said above, poverty, conflict, social relations etc. are seen as the underlying causes for all kinds of sadness, depression, and anxiety. I saw this illustrated-in-reverse most clearly in Kosovo, when a young expatriate psychologist who had just arrived to provide help to the traumatized, had to be consoled by a group of tough Kosovar Albanians. She could not stop crying, and the demobilized soldiers turned to me with guilty and puzzled faces, apologizing: “and so far we have only gotten to our wedding practices…”

So when we are working on mental health we have to stop thinking that ‘mental illness is like any other medical illness’. It is important to realize how a dysfunctional metabolism and neurologic conditions (can and do) affect the mind; it is equally important to understand how the mind is considered as the ‘self’ in different cultures and beliefs, and it is impossible to make sense of all this without recognizing the role of inequity, social injustice and, in many cases, outright violence and repression.

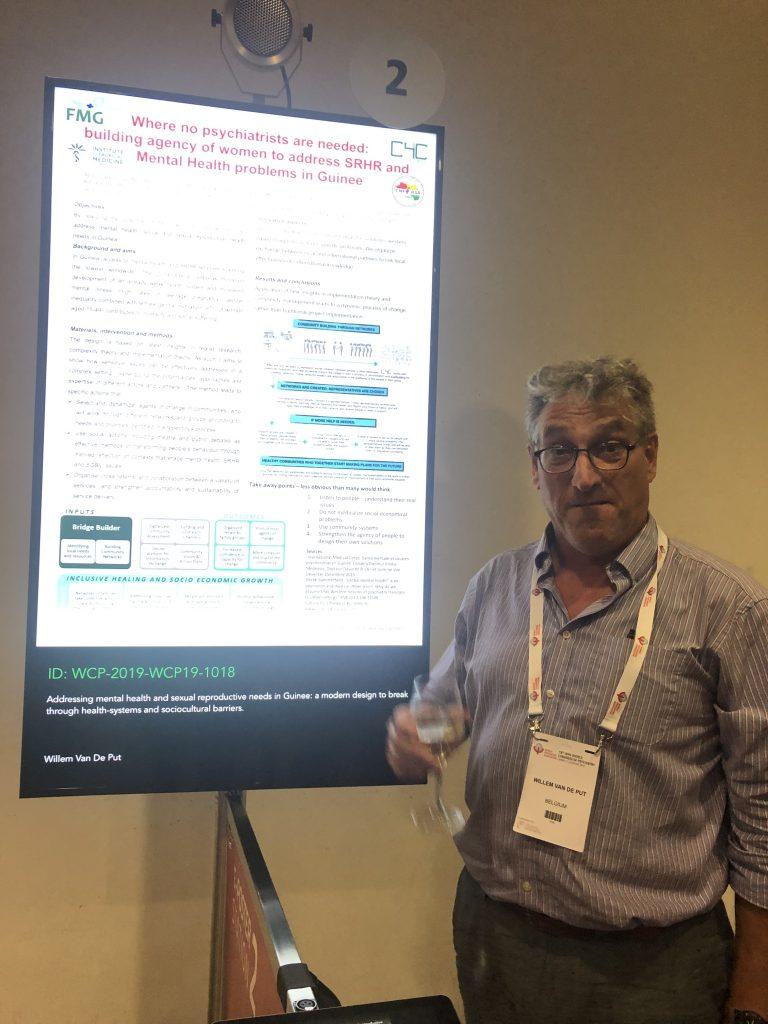

This sounds almost complex – but luckily, complexity is often quite simple. We tried to show this through our two poster presentations (with Abdoulaye Sow, Bart Criel and Bibiane van Mierlo), one on “Integrating mental health services in Guinea through patient centered care” and another one titled, “Where no psychiatrists are needed: building agency of women to address SRHR and Mental Health problems in Guinee”. They both start from an approach that one of our partner agencies in Guinee, FMG, has already been applying for a long time. Based on sound insights in the local community and an intuitive use of the now ‘modern’ ‘5 Cs’ approach, it was perhaps more than a coincidence that ‘patient-centered care’ proved to be one of the focal points of the congress.

In the months and years to come, I hope to further contribute to the integration of mental health in the great NCD programs we have at ITM.